Introduction: the great transformation of finance – what the digital age means for regulators

Being an effective financial regulator in the fintech age is more important and challenging than ever. This is not a transient wave of financial innovation we are witnessing; rather, we are living through a structural transformation of the financial system. Seismic shifts – driven by rapid technological innovation, evolving online habits, more direct buyer-seller interaction through market disintermediation and changing business models in an increasingly complex geopolitical landscape – are reshaping the fabric of the global financial system. Regulators play a pivotal role in this transformation and must adapt swiftly to ensure that innovation is balanced with consumer protection, market integrity and financial stability.

At the heart of this great financial transformation are the ‘ABCD’ technologies: artificial intelligence (AI), big data, cloud computing, and distributed ledger technology (DLT) – each disruptive in its own right. However, when layered with advances in quantum computing and biometrics, the extensive use of application programming interfaces (APIs) and near-universal mobile phone access, they are reshaping the foundational architecture of financial services. Beyond merely altering financial products, services and activities, they are redefining the nature, roles and functions of market participants and structures.

These technological advances combine with shifts in consumer behaviour, cultural norms and socioeconomic conditions to amplify the transformation of finance. Take Generation Z: highly connected digital natives, many of whom now prefer opening accounts with digital-only neobanks, trading on apps[1], investing in meme coins[2] and using social media for ‘getting alpha’[3] (ie generating above-expected returns, given an investment’s risk). Financial preferences are evolving quickly, shaped by instant access, gamification and digitalised social networks.

Recent events illustrate how financial risks can materialise and spread rapidly in this new environment. The 2021 GameStop ‘short squeeze’[4], the 2022 London Metal Exchange nickel crisis[5], the crash of Terra/LUNA[6], the failure of FTX[7], and the 2023 collapses of Silicon Valley Bank[8], Silvergate Bank[9] and Signature Bank[10] are just some examples of how financial stress and risk, in this new context, can quickly ripple outward, due to liquidity pressures, shaking market confidence amplified by social media. Issues that we thought were confined to one corner of finance can morph into global contagions at unprecedented speed. Heightened geopolitical tensions – potentially signalling a new age of geoeconomics,[11] in which political self-interest is blending tech, trade, finance and policies – and other exogenous shocks can expose how interconnected, interdependent and intertwined our financial systems are. Together, these changes compel us to fundamentally rethink how we regulate and supervise financial markets.

The re-constitution of finance: actors, assets, activities and architecture

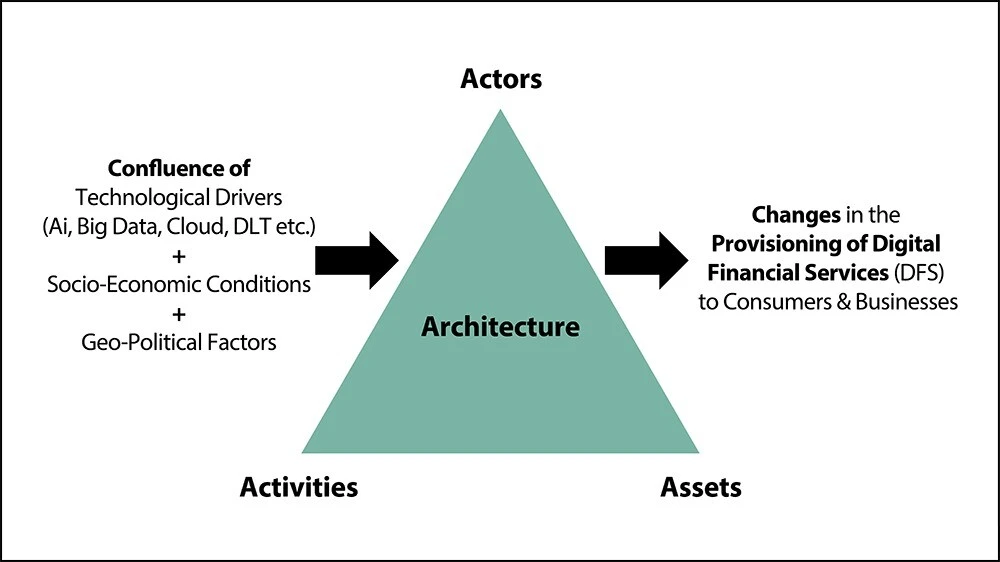

The convergence of technological, socioeconomic and geopolitical drivers has accelerated the digitalisation of financial services. This redefines existing business models and enables and creates new and innovative actors, activities, assets and financial architecture.

Twenty years ago, the cast of actors in financial services was populous but comprehensible: banks, insurers, exchanges and payment processors. Today, the stage is ever more crowded, with the continued growth of non-bank financial institutions (eg investment firms, pension funds, hedge funds, asset managers, private equity, etc). Meanwhile, new players are vying for influence. Fintechs, big tech firms, e-commerce platforms and super apps compete, cooperate and provide critical services to financial companies, creating a complex web of financial relationships, services and dependencies. As well as increasingly diverse actors, the system has gradually moved away from human-based decision-making and control. Automation is quickly becoming autonomous as AI agents, which can underwrite loans or rebalance investment portfolios without human intervention, go mainstream in an era of ‘agentic AI’.

Financial activitiesare also being transformed. The harvesting, processing and use of big data and disintermediation have spurred innovation in product design and a proliferation of novel services. Over the past 10 years, we have witnessed the rise of crowdfunding, marketplace lending, buy-now-pay-later, cross-border digital payments and more recently, financial transactions enabled by open banking, finance and data, as well as early efforts in the tokenisation of money, economic and real-world assets.

The definition of assets has grown beyond fiat money and commercial bank deposits to include stablecoins, tokenised deposits and central bank digital currencies – retail and wholesale. The taxonomy of digital money is expanding rapidly, with cryptocurrencies and enterprise settlement coins further adding to the mix and complexity.

Bringing together these actors, activities and assets with recursive development of the very architectureof financial markets has led to new financial instruments, channels, platforms and centralised or decentralised systems that can exchange data, transfer value, execute contracts and process payments around the clock (see figure 1 below for further illustration of this great financial transformation).

Digitalising actors, activities and assets also directly impacts productivity growth, competitiveness and economic dynamism. The disintermediation and automation of financial services – via agentic AI, cloud computing, smart contracts and open data ecosystems – can lower transaction costs, improve capital allocation and accelerate credit access for micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). Individual consumers of financial services may benefit from greater product choice, improved convenience, greater speed and personalisation.

Whilst digitalisation can boost productivity and spark innovation in the real economy, we must be conscious of the risks that prevent innovation from translating into inclusive, sustainable economic growth, such as market concentration, winner-takes-all dynamics or algorithms making it harder for businesses to compete and could potentially harm consumers. This reinforces accessibility and affordability as key considerations for ensuring the financial health and inclusion of consumers and MSMEs. This is even more crucial in countries where connectivity, digital infrastructure and financial literacy are still developing, so that innovation helps close the digital gap instead of making it wider.

The scale of these changes is extraordinary and unsettling. It begs the question: do public authorities have the right frameworks, capacity and capabilities to regulate and supervise this new and constantly evolving ecosystem of digital financial services? What are the consequences and opportunity costs if we do not get things right?

The ‘innovation delta’: 4 forces driving the divide between regulators and innovators

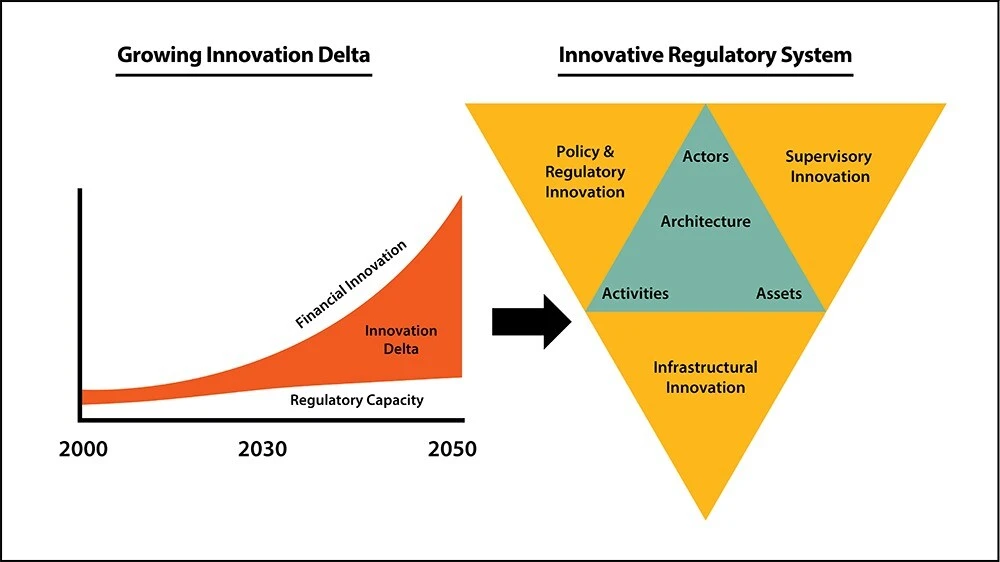

Policy inertia, outdated mandates, regulatory lag, supervisory deficiencies and cross-regulatory complexity are all headwinds in advancing regulatory change. These are risks that we cannot afford. Digital financial services are evolving fast and regulatory authorities are struggling to keep pace, creating a widening ‘innovation delta’. That is the gap between regulators’ capacity to regulate and supervise financial innovation and the rate of financial innovation itself.

The innovation delta is widening, even as central banks and financial regulators worldwide invest heavily in an array of regulatory innovation initiatives. The establishment of innovation offices and regulatory sandboxes in more than 100 jurisdictions, the development and adoption of supervisory technology, and the emergence of regional and global regulatory innovation networks (such as the Bank for International Settlements Innovation Hub (BISIH) and the Global Financial Innovation Network) are crucial initiatives for innovation within regulatory authorities. We are also seeing promising signs of more system-level innovation. Brazil’s Pix system has transformed instant payments[12] while providing better real-time supervisory data and insights. In India, the interplay between digital public infrastructure (DPI), such as Aadhaar and UPI, and account aggregators has enabled more data-led oversight[13]. Respective BISIH projects are experimenting with scaling solutions that could transform our payments and supervisory systems within jurisdictions and cross-border[14]. They offer practical directions for how regulation might evolve iteratively and systemically rather than through piecemeal innovation.

Even so, these initiatives have not been able to reduce the innovation delta. The widening gap reflects how innovators and regulators are misaligned along the lines of institutional and technological architecture, organisational behaviour and ultimately, the capacity to evolve and transform. The innovation delta manifests in 4 key ways:

1

Temporal mismatch

Innovation happens continuously and at an exponential pace. Financial product updates are rolled out daily, payments are now instant and API upgrades are constant. In contrast, regulation remains episodic and capacity building is linear. Legislative and regulatory reform takes years, and supervisory action and enforcement are largely retrospective, relying on ex-post reporting and quarterly or annual figures. The result is a fundamental misalignment of speed and evolution – a ‘structural desynchronisation’ akin to a generational gap, where financial products are born, mature and retire before regulatory frameworks have even come of age.

2

Structural fragmentation

Digital financial services are like LEGO bricks – modular, composable and borderless. In contrast, regulations tend to be rigid and tied to specific jurisdictions. A decentralised platform can now offer lending, asset custody and insurance across multiple jurisdictions through a self-executing smart contract. However, in many instances, regulation remains institutionally siloed by distinct products or activities, with rules and oversight split across national boundaries. This creates challenges for addressing cross-cutting issues such as competition, data protection and the need for co-ordination among different regulators. Regulatory fragmentation can be as significant a barrier to financial innovation as structural shortcomings[15]. The lack of harmonised legal frameworks[16], divergent supervisory practices[17], voluntary global standards subject to local interpretation, outdated mandates, legacy regulatory norms,[18] varying approaches across countries[19] and inconsistent enforcement practices all contribute to this growing gap.

3

Knowledge divides

Regulatory bodies often lack the interdisciplinary teams needed to match the complexity of digital finance. Coders, data scientists, behavioural experts and network theorists are essential, alongside economists and lawyers. The knowledge divide becomes starker around data. Innovators iterate advancements using large volumes of live data, often automating product design. Regulators, on the other hand, rely on static reports and forms. For example, an agentic AI credit model might use data streams (eg geolocation, metadata, psychometrics) that are invisible to regulators, their playbooks and their templates. Regulators must harness talent matching that of the digital banks, big tech firms and fintech companies that regulatory authorities aim to supervise. As regulatory scholar Julia Black has argued,[20] regulatory legitimacy in complex systems depends not just on rule compliance but on ‘epistemic competence’ – the capacity to know what needs to be known to govern effectively.

4

Technological gaps

Regulators are not natural technologists, which poses challenges. In addition to recruiting the right talent to supervise and regulate digital financial services, financial authorities must build a fit-for-purpose and future-proof technology stack. Central banks and financial regulators require the latest technological solutions and platforms and people who know how to use them.

If left unchecked and unchallenged, the innovation delta will widen as financial innovation progresses. Indeed, it will likely be supercharged by new and more capable forms of AI beyond today’s foundation or multimodal models, including generative AI, towards interactive AI, artificial general intelligence (AGI) and artificial superintelligence[21]. Imagine a flywheel that spins with increasing speed as new technologies, actors, activities, assets and architecture continuously reinvent the paradigms that underpin the financial system and broader economy.

The consequences of inaction are severe. When regulation lags behind innovation, it creates space for regulatory arbitrage, jeopardises consumer protection, induces financial instability, weakens public trust in institutions and in principle, makes the financial system more fragile, amplifying systemic tremors. As economies face pressure to boost productivity and growth post-pandemic, regulatory inertia may stifle beneficial innovation, reduce investor confidence and dampen the productivity-enhancing effects of financial technologies. Policy and regulatory objectives – from growth, monetary and financial stability and market integrity to consumer protection, competition and financial inclusion – are all at risk, especially in an era of ‘permacrisis’[22] punctuated with ‘predictable volatility’;[23] this gap is unsustainable.

The great regulatory transformation: From piecemeal to systems innovation

Utilising systems-level thinking and embedding innovation

The current regulatory tools and processes for financial services and the institutional architecture underpinning them were first created and designed from the ground up many decades ago. Since then, the finance ecosystem has become exponentially complex, with the number of systems proliferating – payment, clearing and settlement systems, agentic AI and digital asset ecosystems, etc. Central banks and financial authorities are trying to regulate dynamic, complex and always evolving systems with a linear, siloed, non-digital-first or innovation-driven toolkit, which is essentially giving regulators a garden hose to put out a wildfire.

Faced with disruption, regulators often respond by accelerating existing practices: faster consultations, streamlined licensing regimes, more extensive or improved reporting and more agile supervisory practices. Whilst valuable, this is insufficient.

Piecemeal solutions and fragmented approaches could be helpful in the short term but risk being too disjointed and ineffectual in the face of borderless innovation, data asymmetries, technological gaps and talent shortages. This can result in impaired decision-making, impeded regulatory process and erosion in regulatory capability over the long run.

A shift towards systems-level thinking and embedded innovation is needed. A holistic, integrated, forward-looking approach – that recognises the interconnectivity and complexity of modern finance, its dependency and integration with digital markets, and being driven by internal innovation at the system level – is what’s required. This involves not just focusing on individual financial entities, activities or products but also the broader system in which they operate. It means understanding of how regulatory authorities’ statutory remits, internal processes, capacities and capabilities could co-evolve correspondingly as a ‘living and breathing system’ underpinned by innovation at scale.

In the end, regulatory authorities need to innovate themselves to regulate and supervise financial innovation effectively – the ‘great financial transformation’ necessitates a ‘great regulatory transformation’. This could involve 4 principles for system-level innovation.

4 ways of igniting the great regulatory transformation

1

Embedding innovation into regulation

First, innovation could be embedded and accelerated across the entire regulatory lifecycle – from policy design and rulemaking to authorisation, supervision and enforcement. The ‘innovation premium’ – the added value derived from integrating innovation into regulatory frameworks – may vary across different regulatory and supervisory functions. However, their cumulative impact can be transformative. Over time, these distributed gains can collectively reinvent institutional capabilities and reshape the regulatory architecture.

2

Reinventing organisational processes

Second, innovation should be multi-dimensional and holistic, encompassing technological advancements such as platforms, solutions, and digital infrastructure, as well as the digitalisation and redesign of processes and procedures. Equally critical are organisational innovations, including investments in human capital through capacity building and training, and the often overlooked but essential shifts in mindset and cultural transformation, including incentivising individuals to drive institutional changes.

3

External collaboration

Third, innovation is not confined to internal processes – it must also extend outward through purposeful collaboration, thoughtful modernisation of regulatory frameworks and periodical reassessment of regulatory mandates and perimeters. This collaboration should strengthen coordination within and across regulatory agencies to ensure aligned approaches around policymaking, supervision, enforcement and data governance. It also calls for deeper cross-regulatory, regional and international engagement to exchange knowledge, pilot joint initiatives and shape interoperable standards. Just as importantly, regulators must learn from and when appropriate, partner with fintechs, incumbents, technologists and academics to embed cutting-edge insights into regulatory design and harness the power of public-private partnerships.

Regulatory innovation is not merely a technocratic imperative – it is also an economic enabler. Competitive economies require adaptive regulators that can safeguard stability without stifling innovation. Recalibrating regulators’ mandates in certain cross-cutting areas, beyond traditional prudential and conduct oversight, to better reflect a rapidly changing financial ecosystem would ensure they remain fit for purpose and support more agile, forward-looking supervisory approaches. International firms and investors increasingly assess regulatory environments when deciding where to launch new products, scale operations or allocate capital. Countries that lag in regulatory and supervisory innovation may see diminished competitiveness, while those that lead can attract high-quality firms and talent, contributing to economic growth.

4

Systemic innovation and evolving regulation

Finally, innovation must operate at the level of systemic redesign and institutional re-engineering. Isolated pilot projects, upgraded technologies and ad-hoc upskilling – even when ambitious – cannot by themselves deliver the profound reinvention or ‘system upgrade’ required to narrow the innovation delta. Rather than solutions, we should be thinking about a stack; rather than fixes and patches, we should be building foundations and designing architectures.

Ultimately, central banks and financial regulators need to build their own innovative regulatory systems with new institutional architectures and capability stacks underpinned by sustained policy, regulatory, supervisory and infrastructural innovations (see figure 2 for further illustration). These should not be in isolation but mutually reinforcing. These new systems must also be able to expand, re-adjust and evolve, just like the financial innovation and digital financial services they aim to regulate and supervise.

5 key pillars of innovative regulatory systems

What are some of the key pillars of these innovative regulatory systems capable of evolving with the development of digital financial services?

1

Modular, adaptive, iterative and anticipatory[24] policy and regulatory systems

Frameworks that can move with the speed of change, flex with risk and build upon themselves.

Regulation would be dynamically configurable by use case, risk and scale, informed by real-time data, empirical evidence and robust analytics. Regulatory sandboxes could become permanent testbeds, highly integrated with authorisation and supervision. Dynamic licensing could evolve with firm risk profiles. Prefabricated policy and regulation templates could draw on real-time data feeds and become composable regulatory LEGO bricks to create new regulatory regimes to adapt to new financial actors or instruments without rewriting foundational statutes. Further, as market conditions shift or data thresholds are breached, policy elements would self-update within pre-defined bounds – akin to monetary policy rules responding to inflation bands. Notably, a degree of regulatory predictability would be essential for market confidence and compliance feasibility. To achieve that, frameworks should be underpinned by regulatory clarity, transparent guardrails and robust oversight mechanisms.

2

Machine-readable and machine-executable regulation

From policy PDFs to programmable protocols, regulation would be structured, where appropriate, as formal code.

It would be tagged, indexed and standardised in a format that AI-enabled systems can process. Regulators would publish API endpoints to push rule updates to market actors instantly, rather than periodic PDF publications. With maturity, this will lead to machine executability, where compliance rules embedded in financial platforms or infrastructures automatically validate behaviour, log anomalies or trigger canned responses. Of course, institutions would remain responsible for their compliance. They would need to have frameworks to ensure that not just the letter of the law but the spirit of regulation is followed. Importantly, this shift would enable real-time enforcement, lower compliance friction and allow regulators to monitor systemic behaviour, complementing traditional firm-level supervision and interventions.

3

Proactive and embedded supervision through intelligent infrastructure

Systemic and always-on oversight, not episodic.

Supervision would shift from periodic audits to real-time, direct, automatic monitoring of the market ledgers for compliance verification. Suptech solutions, toolkits, platforms and infrastructure can work in sync and deliver live insights, anomaly detection and systemic risk visualisations. Integrating supervisory systems with DPI and data-sharing systems (eg open banking, open finance, and real-time and government-to-person payments) can enable predictive and even prescriptive oversight. The Central Bank of Brazil gains timely insights into economic activity and consumer behaviour through its instant payments ecosystem Pix[25] – enhancing regulatory supervision, market monitoring and macroeconomic nowcasting while improving its ability to respond to emerging trends and risks.

4

Interdisciplinary talent and constant institutional learning

Build financial authorities that can think and work laterally and learn as markets do.

Regulators of the digital era need multidisciplinary teams – lawyers who understand code, economists who model decentralised finance networks and supervisors who can interpret behavioural signals – with incentives to adapt and drive change. Regulators would adopt learning agendas, digital credentials, simulation environments and internal hackathons to test and learn. AI tools can assist and we might have AI supervisors in the future but human capability, oversight and accountability (i.e. human in the loop) will remain vital. Cultural shifts and changes in mindset would be key enablers in building continuous learning institutions.

5

Collaborative regulatory and supervisory solutions and processes

No regulator is an island and supervision must scale across borders and silos.

Financial innovation knows no boundaries. Intra-agency, inter-agency and cross-border regulatory coordination and collaboration should be baked into system design. Co-operation between data and competition authorities and other bodies overseeing digital markets will be critical (eg the UK Digital Regulatory Cooperation Forum[26]). This step change in collaboration would be characterised by interoperable taxonomies and common data standards (eg ISO 20022 for payments), joint sandbox environments for cross-border testing and an evolution of secure data sharing protocols that preserve privacy but enable further insight.

These 5 pillars do not mean abandoning core principles and policy objectives such as prudential soundness, consumer protection, market integrity or monetary and financial stability. Instead, innovative regulatory systems aim to achieve these objectives more effectively. Innovative regulatory systems do not imply either deregulation or over-regulation but proportionate, risk-based, data-led and outcome-focused regulation and supervision. Human factors – judgement, collaboration, independence – should not be sacrificed for speed. Under many circumstances, slowness is both necessary in terms of legislative processes and essential for evidence-based and proportionate policymaking and regulation.

With emerging markets and developing economies in mind, inclusion and accessibility are also essential for designing and developing innovative regulatory systems in environments with very limited connectivity, institutional capacity and financial resources. Innovation without inclusion is incomplete and in the end, financial services should provide accessible and affordable products for consumers and businesses (especially MSMEs), enabling them not only to get by but also to thrive. To ensure economies at all stages of development can benefit, innovative regulatory systems should focus on adaptability and scalability supported by shared infrastructure, solutions transfer and regulatory collaboration.

The moonshot: ‘Regulatory singularity’ and the end of the innovation delta

What is the end goal of regulatory innovation and what kind of system are we ultimately striving for?

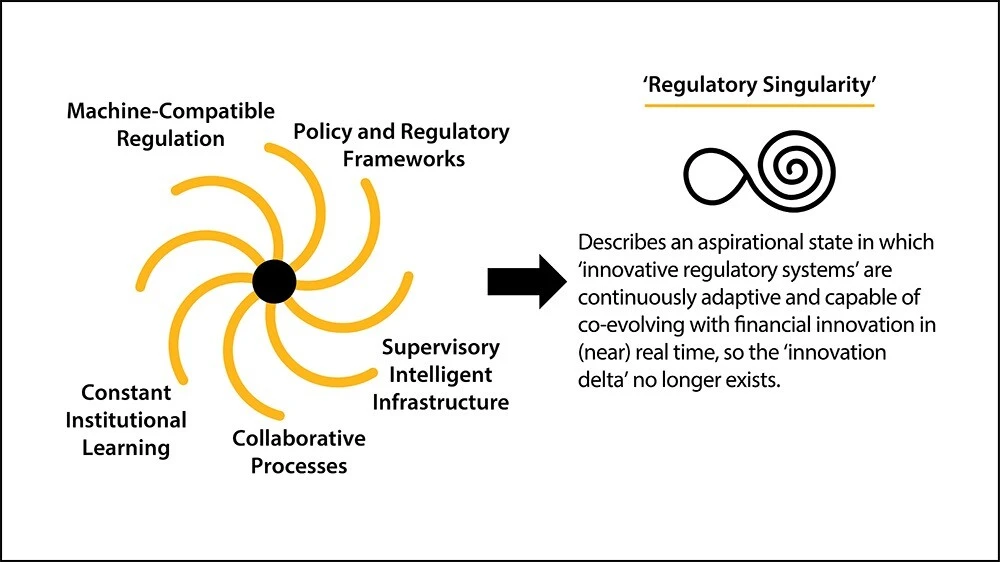

The moonshot for these innovative regulatory systems is a state of ‘regulatory singularity’: an aspirational future in which regulatory systems are continuously adaptive and capable of co-evolving with financial innovation in (near) real time, effectively eliminating the innovation delta. This vision can gain early momentum in areas like real-time payments and smart contract-based transactions, where digital infrastructure and programmability already enable rapid regulatory and supervisory feedback and adaptation.

This envisioned future sees the pace of innovation within public authorities synchronise with that of the marketplace. Regulatory institutional architecture would mirror the structure and dynamics of financial markets. Regulators’ capabilities would scale as needed, shrinking the gap between emerging risks and enforceable action to virtually zero (see figure 3 below for further illustration). Regulatory singularity is not just about governance or compliance – it is about creating the conditions for sustained economic growth, entrepreneurial dynamism and global competitiveness. In a future where financial services underpin digital economies, effective regulation can become a comparative advantage. Jurisdictions that can match regulatory capacity with market innovation will not only close the innovation delta but also unlock new frontiers of productivity and prosperity.

‘Singularity’ is a term with roots across mathematics, economics, finance and astrophysics and it is also a nod to singularity in AI development as we will probably live through the realisation of AGI over the next 5 or 10 years.[27] We need to start planning and preparing for that near future. Therefore, piecemeal or incremental approaches are no longer sufficient.

Regulatory singularity may be seen as utopian and not achievable in reality. In an increasingly fragmented, geopolitically tense world, institutions with tightly defined legal mandates may find it even harder to innovate, let alone evolve. So, it could be that these moonshots fall short. Still, regulatory singularity serves a vital purpose as an aspiration, a strategic horizon, a heuristic tool and a vision to strive towards. It can spur action, catalyse system-level design and embed institutional-wide innovation, minimising the innovation delta.

Ambition to action – 5 practical steps for system-level regulatory innovation

The innovation delta is not inevitable – we already have many building blocks in place. The real challenge is moving from innovation at the margins to transformation at the core of regulatory systems. Moving from pilots to platforms, sandboxes to systems, innovation in isolation to innovation through collaboration is essential.

How do we begin this journey? It starts with understanding the art of the possible by systematically sharing best practices and lessons learned from public authorities across the globe that are fostering innovation. Importantly, we must look at emerging markets and developing economies as well as advanced economies. In many cases, central banks and regulators in the Global South have moved faster and more creatively, pioneering innovative policy frameworks and regulatory solutions that have leapfrogged those of their peers in more developed jurisdictions[28]. In essence, we need a ‘global regulatory innovation knowledge depository’ – an open-access GitHub-like storeroom of innovation experiences, practices and lessons to enable peer learning and knowledge transfer.

Second, regulators need to co-develop practical policy templates, regulatory toolkits, supervisory platforms and shared digital infrastructure that speed experimentation, streamline procurement, lower costs, widen adoption and ease technology transfer across jurisdictions. Think of this as a joint regulatory innovation huballowing financial authorities to co-procure, co-design, test and iterate, and co-own shared regulatory LEGO sets, transferrable frameworks and technological solutions. To put it differently, we need a collective procurement model that lets regulators pool resources, co-develop solutions and share the benefits.

If we go a step further, we can create a ‘digital regulatory commons’ – a shared stack with layers of standards, frameworks, analytics and tools that anchor cross-border policy alignment, regulatory co-ordination, supervisory collaboration and industry engagement. For instance, in AI regulation and supervision, we will need to build the regulatory equivalent of an open innovation stack combining the functions of a model hub akin to Hugging Face, a testing and benchmarking arena like Kaggle and a cloud-based experimentation and deployment environment such as Colab – purpose-built for regulators and supervisors.

In an era of geopolitical fragmentation, a digital regulatory commons could help standard-setting bodies build consensus and jurisdictions adapt international standards. This would particularly benefit financial and non-financial regulators in emerging markets, enhancing their ability to scrutinise risks and freeing capacity to focus on innovations to leapfrog developed markets. Developed market regulators would be liberated to build capacity and capability to reduce the knowledge divide, collaborate internationally and shift their work towards surveillance and prevention.

Third, with shared infrastructure and analytical capabilities, it is not inconceivable that one day, central banks, financial regulators and supervisory agencies could significantly increase the volume, cadence and scope of data, information and intelligence sharing and exchange for licensing, supervision and enforcement purposes, both intra- and inter-agency. This will enable the opening of subscription-only ‘walled gardens’; enhanced connectivity and synchronisation between databases, data lakes and data warehouses; and the development of real-time, always-on ‘regulatory and supervisory super intelligence’ that will have a fair fight against globalised financial crimes in the AGI era.

Fourth, we must learn faster together. Capacity building and education at scale via digital channels will be key to creating adaptive regulators and learning regulatory institutions. Just as we might need to pool resources and co-procure innovative technological solutions, central banks and financial regulators can also pool their talents through secondment programmes, exchange opportunities and project-based sprints and programmes, as BISIH has successfully piloted and demonstrated. There are many internal academies and training schools within the boundaries of regulatory authorities, as well as unconnected capacity-building programmes by various stakeholders in the ecosystem, which can result in duplication. What we perhaps need is to combine forces and create a series of digital-first and highly co-ordinated strategic innovation training programmes with a long horizon and delivered via a network ofcapacity-building clusters.

Fifth, we should foster a culture of regulatory co-ordination by leveraging digital-first collaborative platforms and building communities of practice and innovation across sectors, regulatory mandates and borders. For instance, the Regulator Knowledge Exchange platform hosted by the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance[29] already has 2,800 regulator members from over 200 regulatory authorities, who utilise the digital community platform to connect, co-ordinate, learn and collaborate on a peer-to-peer level and institutionally. Without peer-to-peer networks, connections and a sense of community, the spirit of innovation and the culture of collaboration are unlikely to be sustained.

Looking ahead

If we approach the financial regulation-innovation challenge at this moment with strategic and tactical ambition – staying nimble, agile, collaborative and imaginative while taking small, deliberate steps – we can ignite the great regulatory transformation. By innovating at the system level, we can gradually shift from linear regulation to an iterative, adaptive model powered by innovative regulatory systems. As these systems evolve to match the speed and complexity of digital finance, we edge closer to regulatory singularity: a future where regulation is as dynamic, attuned and evolving as the systems it seeks to govern.

Let us begin.

Featured author

Bryan Zheng Zhang

Co-Founder and Executive Director, Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance, Cambridge Judge Business School

Acknowledgement

This article was adopted from two keynote presentations delivered respectively on 23 April 2025, during a special session at the 61st Meeting of the Network of Central Banks and Finance Ministries of Latin America and the Caribbean, hosted by the Inter-American Development Bank; and on 12 May 2025 at the Dubai FinTech Summit. This article has benefitted considerably from the support and comments of Matthew Jones, Hugo Coelho, Pavle Avramovic, Jon Frost, Hunter Sims, Nick Clark, Caroline Malcolm, Kieran Garvey, Philip Rowan, Eilis Ferran, Douglas Arner, Lotte Schou Zibell, Timothy Lane, Diego Herrera, Keith Bear, Siddharth Shetty, Keith Barnes, Sanya Juneja and Sophia Akram. All errors and omissions remain my own. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of author alone and do not represent and should not be attributed to the institutions that I work for or associated with.

Related articles in this series

Read more articles from the CCAF Perspectives series.

Industry leaders face a choice: act now or risk the integrity of blockchain-based markets and digital currencies, says Wenbin Wu, Research Associate at the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (CCAF), Cambridge Judge Business School. Here we reveal regulators’ and policymakers’ bridging roles for quantum-resilient blockchains, and the importance of collaboration by technologists, economists, and regulators in the quantum age of financial technology.

AI and technology

How can AI in finance realise its full potential?

Kieran Garvey, AI Research Lead at the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (CCAF), and Bryan Zhang, Co-Founder and Executive Director of CCAF, explore why banks struggle to turn AI efficiency into growth.

AI and technology

Innovation to impact: technology, governance and regulation

As governments worldwide grapple with the accelerating pace of technological change, the central challenge is no longer technical but institutional: how to translate digital innovation into citizen-first outcomes at scale. The obstacles lie in execution – requiring effective governance, adaptive regulation, and institutional transformation. In this piece, Carlos Montes (Lead – Cambridge Innovation Hub for Prosperity), Montek Singh Ahluwalia (citizen-first public servant and economic reformer), and Pavle Avramovic (Head of Market and Infrastructure Observatory at the CCAF), examine how public institutions can move from policy ambition to real-world impact by building innovation-ready systems that prioritise citizens over processes

To cite this article please use the following:

Zhang, B.Z. (2025) From innovation delta to regulatory singularity: How innovative regulatory systems can help regulation keep pace with financial innovation. Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance, University of Cambridge Judge Business School

Endnotes

[1] CFA Institute FINRA Investor Education Foundation Zeldis Research (23 May 2023) ‘Gen Z and Investing: Social Media, Crypto, FOMO, and Family’, CFA Institute Research & Policy Center. Available at: https://rpc.cfainstitute.org/research/reports/2023/gen-z-investing

[2] Bonos, Lisa (4 May 2025) ‘These young people see meme coins as their best shot at the American Dream’, The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/05/04/crypto-meme-coins-investing-wealth/

[3] CFA Institute FINRA Investor Education Foundation Zeldis Research (23 May 2023) ‘Gen Z and Investing: Social Media, Crypto, FOMO, and Family’, CFA Institute Research & Policy Center. Available at: https://rpc.cfainstitute.org/research/reports/2023/gen-z-investing

[4] Desiderio, Antonio; Aiello, Luca Maria; Cimini, Giulio; and Alessandretti, Laura (3 February 2025) ‘The dynamics of the Reddit collective action leading to the GameStop short squeeze’, Nature. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s44260-025-00029-z

[5] Reuters (20 March 2025) ‘UK fines LME nearly $12m over handling of 2022 nickel crisis’, Mining Weekly

[6] Yaffe-Bellany, David (18 May 2022) ‘How a Trash-Talking Crypto Founder Caused a $40 Billion Crash’, The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/18/technology/terra-luna-cryptocurrency-do-kwon.html

[7] Helmore, Edward (28 March 2024) ‘“Old-fashioned embezzlement”: where did all of FTX’s money go?’, The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2024/mar/27/where-did-ftx-money-go

[8] Hetler, Amanda (13 March 2024) ‘Silicon Valley Bank collapse explained: What you need to know’, TechTarget. Available at: https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/feature/Silicon-Valley-Bank-collapse-explained-What-you-need-to-know

[9] Knauth, Dietrich (18 September 2024) ‘Silvergate Capital enters bankruptcy after crypto bank’s shutdown’, Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/legal/litigation/silvergate-capital-enters-bankruptcy-after-crypto-banks-shutdown-2024-09-18/

[10] Son, Hugh (13 March 2023) ‘Why regulators seized Signature Bank in third-biggest bank failure in U.S. history’, CNBS. Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2023/03/13/signature-bank-third-biggest-bank-failure-in-us-history.html

[11] Tett, Gillian (9 May 2025) ‘Welcome to the new age of geoeconomics’, Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/daf5ce11-c95b-4964-8df1-7463f0f9a81b

[12] Banco Central do Brasil Working Paper No. 564: ‘Nowcasting Brazilian GDP with Electronic Payments Data’. (See: https://www.bcb.gov.br/pec/wps/ingl/wps564.pdf)

[13] Ministry of Finance, Government of India. (2025) Annual Report 2024–25. Department of Financial Services. Available at: https://financialservices.gov.in/beta/sites/default/files/2025-05/Annual-Report-2024-25.pdf

[14] BIS (2025) About the BIS Innovation Hub (See: https://www.bis.org/about/bisih/about.htm?m=265)

[15] White, H. (2025) ‘Wall Street regulation needs a rethink under Donald Trump’, Financial Times, 13 January. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/5d050c76-db89-48f4-a311-a71b3686f3f3

[16] Ringe, W.-G. and Ruof, C. (2020) ‘Regulating Fintech in the EU: The Case for a Guided Sandbox’, European Journal of Risk Regulation, 11(3), pp. 604–629. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2020.8

[17] Vijayagopal, P., Jain, B. and Ayinippully Viswanathan, S. (2024) ‘Regulations and Fintech: A Comparative Study of the Developed and Developing Countries’, Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(8), 324. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17080324

[18] Bains, P. and Wu, C. (2023) ‘Institutional Arrangements for Fintech Regulation: Supervisory Monitoring’. Fintech Notes No. 2023/004. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fintech-notes/Issues/2023/06/23/Institutional-Arrangements-for-Fintech-Regulation-Supervisory-Monitoring-534291.

[19] For example, stablecoins are categorized as securities in some jurisdictions and as deposit-like products in others.

[20] Black, Julia, Constructing and Contesting Legitimacy and Accountability in Polycentric Regulatory Regimes (February 2008). LSE Legal Studies Working Paper No. 2/2008, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1091783.0 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1091783; Baldwin, Robert and Black, Julia (2008) Really responsive regulation. Modern Law Review, 71 (1). pp. 59-94. ISSN 0026-7961 DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2230.2008.00681.x

[21] Bostrom, N. (2014) ‘Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies’

[22] Brown, G., El-Erian, M. A., & Spence, M. (2023). ‘Permacrisis: A Plan to Fix a Fractured World (with R. Lidow)’. London: Simon & Schuster UK Ltd.

[23] Rathi, N. (2024) ‘Predictable volatility’, Financial Conduct Authority. Delivered at the FCA International Capital Markets Conference, London, 8 October. Available at: https://www.fca.org.uk/news/speeches/predictable-volatility.

[24] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (n.d.) ‘Anticipatory governance‘. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/anticipatory-governance.html

[25] Banco Central do Brasil Working Paper No. 564: ‘Nowcasting Brazilian GDP with Electronic Payments Data’. (See: https://www.bcb.gov.br/pec/wps/ingl/wps564.pdf)

[26] UK Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum (DRCF): https://www.drcf.org.uk/

[27] Kurzweil, R. (2005) ‘The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology’. New York: Viking.

[28] IMF (2023) ‘Digital Financial Innovation and Inclusion in Emerging Markets’.

[29] Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (CCAF) (2025) ‘Regulator Knowledge Exchange (RKE) platform overview’. Available at: https://www.jbs.cam.ac.uk/faculty-research/centres/alternative-finance/regulator-knowledge-exchange/