Introduction

Climate change is no longer a distant threat – it is already reshaping economies, societies, and ecosystems. Under current policies, global warming could exceed 3°C, resulting in macroeconomic losses of at least 18% of global GDP by 2050[1]. Conversely, with the right action, significant economic value could be created through effective investment in the climate transition.[2]

Businesses, consumers and investors each play a critical role in strengthening our economies and societies against the impacts of climate change. In this article, we explore finance’s role in facilitating the climate transition, examine the scale of the challenge, highlight the key actors involved, and clarify fundamental definitions that underpin this topic.

The context

Since the industrial revolution, modern economies have relied on energy sources and industrial methods emit large volumes of greenhouse gases. These practices both warm the planet and erode the natural capital and biodiversity essential for life on earth. As temperatures rise, the environment’s capacity to provide crucial ecosystem services such as food supply, water purification, climate regulation and flood control diminishes, threatening human well-being and survival. Put differently, our global operating model is at odds with the preservation of the resources on which it relies. In recognition of these challenges, global treaties have been put in place seeking to limit or reverse the contributors to, and impacts of, climate change.

1994

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), ratified by 196 countries in 1994, was the first global treaty designed to combat climate change[3].

1997

This paved the way for the Kyoto Protocol (1997), which obliged industrialised countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

2016

Building on these frameworks, the Paris Agreement (2016) seeks to keep global temperature rise well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, with efforts to restrict the increase to 1.5°C and aims to align financial flows with a low-emission, climate-resilient future, so-called ‘Paris Aligned’ investments[4].

However, things aren’t going so well…

2025

While countries pledge new emissions reductions at each Conference of the Parties (COP), practical pathways to achieve these targets are often undefined. Businesses and countries are adapting too slowly, and public and private sector investment levels are nowhere near the amounts required to avoid the impacts of significant climate change.

20..?

The future, and our pathway to 2030 and 2050 climate goals remain highly uncertain. Actual GDP losses may exceed current projections once compounding effects, stranded assets, and biodiversity loss are fully considered.

The role of finance in the climate transition

According to the UNFCC, Climate Finance is the local, national or transnational financing that seeks to support mitigation and adaptation actions that will address climate change. Mitigation activities include reducing or avoiding greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions or enhancing ‘sinks’, which remove GHGs from the atmosphere. Adaptation aims to reduce the vulnerability of human or natural systems to the impacts of climate change and climate-related risks, by increasing resilience and responding to risks.

Meeting current climate commitments will require USD 8.6 trillion[5] of global climate finance annually between now and 2030, and over USD 10 trillion annually in the 2030s. Developing countries alone need USD 2.4 trillion annually by 2030, yet pledges from developed nations remain insufficient and lack transparent sourcing or deployment strategies[6]. With every year of underinvestment, these numbers continue to climb. At the annual Conference of Parties (COP) 29, developed countries committed to fund developing nations to the tune of $300 billion per year by 2035 with aspirations to reach USD 1.3tn[7]. Not only does this significantly under-address the issue, but there has also been limited diligence or data on how exactly these committed funds will be sourced or deployed.

To address the urgent need for real-world decarbonisation, we define ‘transition finance’ as capital deployed to help high-emitting industries and economies evolve toward sustainable business models, production and consumption methods which align with long-term climate goals.

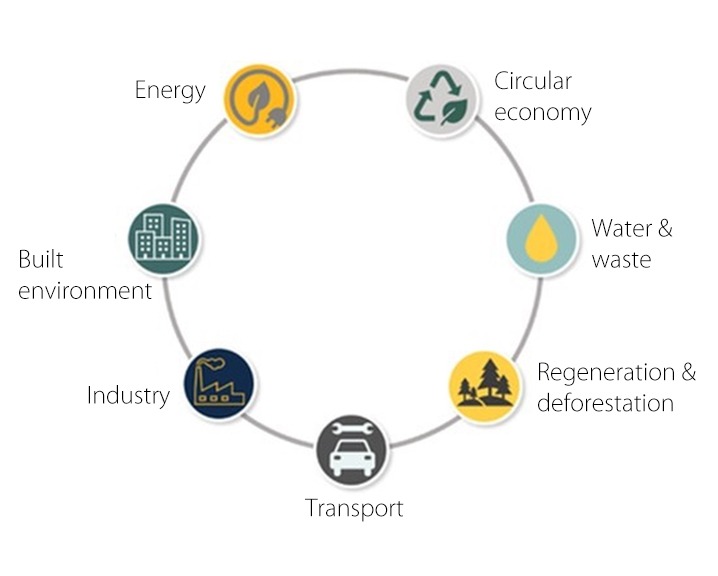

This includes:

Energy

Decarbonising energy production and use. Moving to renewables and alternative sources. Upgrading grid and storage capacity to hold clean energy and improving access in rural areas.

Built environment

Transitioning buildings to cleaner and more energy efficient structures, technologies, construction materials and methods.

Industry

Adoption of cleaner technologies and processes to manufacture and produce goods and materials such as steel and cement.

Transport

Electrifying transportation systems and exploring solutions such as sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) for harder-to-electrify modes of transport.

Regeneration and reforestation

Restoring degraded ecosystems to their natural state, enhancing biodiversity, and increasing their capacity to absorb carbon.

Water and waste

Management of water resources and waste systems to reduce emissions, improve efficiency, and minimise environmental impact.

Circular economy

The development of non-linear business models which enable resource reuse, recycling and minimal waste.

Transition finance is essential to ensure that industries responsible for a large share of global emissions can, and will, decarbonise. Achieving net-zero goals will require annual clean-energy and industrial decarbonisation investments of USD 4 trillion by 2030[8]. Whilst many businesses are making commitments, research shows that corporate climate pledges often lack credibility unless backed by concrete action or investment plans[9]. A significant part of this challenge lies in ensuring that financial flows are directed toward meaningful and measurable climate action and in identifying which solutions will achieve maximum impact.

Who is investing and where is it going?

The transition finance landscape is evolving rapidly, and in many markets data collection remains a complex process, with a lack of consistent reporting limiting transparency. Organisations such as the Climate Policy Initiative, Dark Matter Labs and Our World in Data, alongside larger data providers such as Bloomberg, have begun to demystify these capital flows through primary data collection efforts.

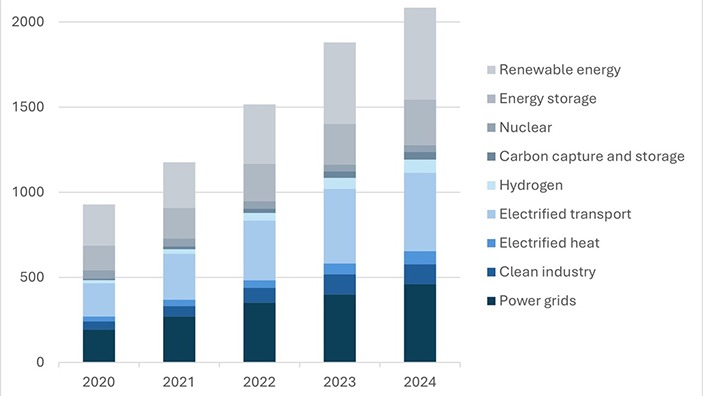

In 2024, global transition investment reached $2.1 trillion – an 11% increase from the previous year – primarily directed at clean energy and transport solutions[10].

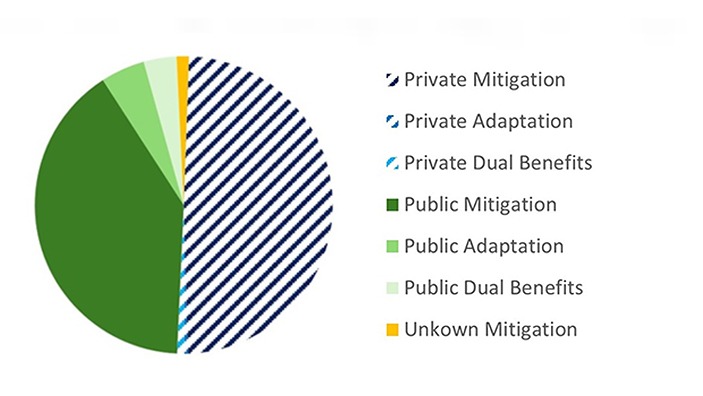

Despite rising investments, the current scale is insufficient to meet global transition targets. The ratio of public to private capital contributions remains roughly 1:1, whereas developing markets need ratios of at least 1:8[11]. Investment by public and private-sector capital owners are also predominantly focused on mitigation activities, with approximately 10% of capital going to adaptation or ‘dual benefits’ use cases. Adaptation projects are typically complex with higher risks and less clear avenues for financial returns but are necessary for reaching a net zero future.

Geopolitical shifts and partisan debates have put public sector climate investment under pressure as governments face intensifying competition within tightening budgets funds are becoming more prominent. At the same time, partisan views around the importance and relevance of climate change, and perceived conflicts with economic growth, are affecting the investment landscape for corporates and private investors. This makes demonstrating viable returns and robust business cases even more important to unlock large-scale investment.

Investor perspectives

What can drive investors to deploy more capital?

Some of the challenges to overcome include lack of discoverability of projects, a mismatch in supply and demand of capital types, and a lack of consistency on taxonomies and impact measurement approaches which make assessing and monitoring investments challenging. Beyond the ethical and environmental benefits, and financial returns, compelling reasons to invest include managing climate-related risks and meeting regulatory requirements. As regulators impose further disclosure and reporting requirements on investors, the ability to classify and distinguish between green and non-green investments will become more important than ever. The confluence of regulatory and policy imperatives, with financial incentives and capital growth opportunities, will ultimately drive private sector capital flows at scale.

Conclusion

Climate and transition finance are essential to address the challenges of climate change. Investing in the transition is complicated and requires new approaches to succeed at scale and bridge the gap between today’s high-carbon industries and the low-carbon future. The Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (CCAF) explores how diverse capital structures, systems thinking, and supportive policies could help meet these pressing needs.

Featured author

Philippa Martinelli

Head of Climate & Transition Finance, Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance

Related content

An early version of this articlewas published via CCAF LinkedIn on 10 April 2025.

Related articles in this series

Read more articles from the CCAF Perspectives series.

Industry leaders face a choice: act now or risk the integrity of blockchain-based markets and digital currencies, says Wenbin Wu, Research Associate at the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (CCAF), Cambridge Judge Business School. Here we reveal regulators’ and policymakers’ bridging roles for quantum-resilient blockchains, and the importance of collaboration by technologists, economists, and regulators in the quantum age of financial technology.

AI and technology

How can AI in finance realise its full potential?

Kieran Garvey, AI Research Lead at the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (CCAF), and Bryan Zhang, Co-Founder and Executive Director of CCAF, explore why banks struggle to turn AI efficiency into growth.

AI and technology

Innovation to impact: technology, governance and regulation

As governments worldwide grapple with the accelerating pace of technological change, the central challenge is no longer technical but institutional: how to translate digital innovation into citizen-first outcomes at scale. The obstacles lie in execution – requiring effective governance, adaptive regulation, and institutional transformation. In this piece, Carlos Montes (Lead – Cambridge Innovation Hub for Prosperity), Montek Singh Ahluwalia (citizen-first public servant and economic reformer), and Pavle Avramovic (Head of Market and Infrastructure Observatory at the CCAF), examine how public institutions can move from policy ambition to real-world impact by building innovation-ready systems that prioritise citizens over processes

Endnotes

[1] (2021) “World economy set to lose up to 18% GDP due to climate change if no action taken, reveals Swiss Re Institute.” Swiss Re Institute

[2] (2025) “Ambitious climate action could boost global 2040 GDP by 0.2%, says OECD study.” Reuters

[3] (n.d.) “The Paris Agreement.” UNFCCC

[4] (2023) “What You Need to Know About World Bank Group Alignment with the Paris Agreement.” World Bank

[5] (2023) “Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2023.” Climate Policy Initiative

[6] (2024) “Raising ambition and accelerating delivery of climate finance.” Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance

[7] (2024) “COP29 agrees $1.3tn climate finance deal but campaigners brand it a ‘betrayal.’” The Guardian

[8] (2021) “Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector.” International Energy Agency

[9] (2022) “SBTi Monitoring Report 2022.” Science Based Targets Initiative

[10] (2024) “Energy Transition Investment Trends 2024.” BloombergNEF

[11] (2023) “Scaling up Blended Finance for Climate Mitigation and Adaptation in EMDEs.” Network for Greening the Financial System