New data on global Bitcoin mining released by the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (CCAF) as part of the Cambridge Digital Assets Programme (CDAP) confirms the growing dominance of the US and reveals a surprising resurgence.

New mining map data, spanning the period from September 2021 to January 2022, included shows that the US has remained at the forefront of Bitcoin mining and extended its leading position (37.84%) amidst the global hashrate recovery. Following a sudden uptick in covert mining operations after the June 2021 government-mandated ban on Bitcoin mining, China has re-emerged as a major mining hub (21.11%). Kazakhstan (13.22%), Canada (6.48%), and Russia (4.66%) have been relegated to more distant places.

Remarkable hashrate recovery results in new all-time high

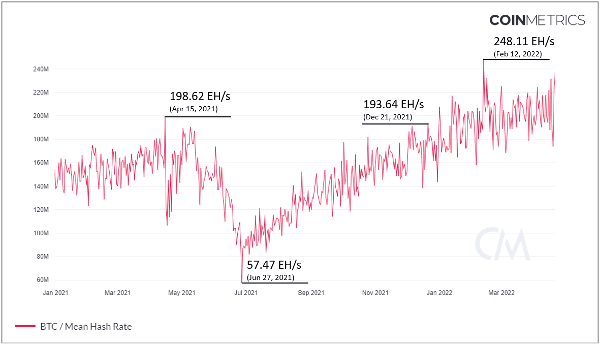

When we released the last update of the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (CBECI), mining map in October 2021 (covering data up to the end of August 2021), the Bitcoin network was grappling with the consequences of the Chinese ban on domestic mining activities. The government crackdown immediately resulted in a harsh decline of the total hashrate – the network’s aggregate computing power – which bottomed at 57.47 Exahashes per second (EH/s) on 27 June 2021.

However, the trend quickly reversed as miners began to relocate operations abroad, and by the end of the year, total network hashrate had almost fully recovered to pre-ban levels (193.64 EH/s on 21 December 2021). What’s more, the upward trajectory continued in early 2022 and culminated in a new all-time hashrate high of 248.11 EH/s in February, demonstrating considerable resilience and flexibility of the Bitcoin mining industry. As a result, it is worth noting the distinction between absolute hashrate levels and relative country shares when analysing country-specific developments: a shrinking country share does not necessarily imply a decline in domestic mining activities but may rather indicate stagnation or slower growth relative to the rest of the world.

Now, exclusive data obtained in collaboration with partnering mining pools BTC.com, Poolin, ViaBTC (1), and Foundry provides new insights into the whereabouts of this new hashrate capacity. As the remainder of this post will show, it turns out that the hashrate recovery has not been distributed evenly.

US extending its leading position as the largest mining hub globally

New data confirms that the United States has not only retained its leading position as the largest mining hub globally, but also surpassed the rest of the world in terms of hashrate growth. This is evidenced by installed capacity surging from 42.74 EH/s (35.40%) in August 2021 to 70.97 EH/s (37.84%) in January 2022. But even prior to the Chinese crackdown, increases in US hashrate (from 15.74 EH/s in January to 26.18 EH/s in June) have outpaced overall network growth, leading to a significant gain in hashrate share from 10.55% to 21.81% over the first half of 2021.

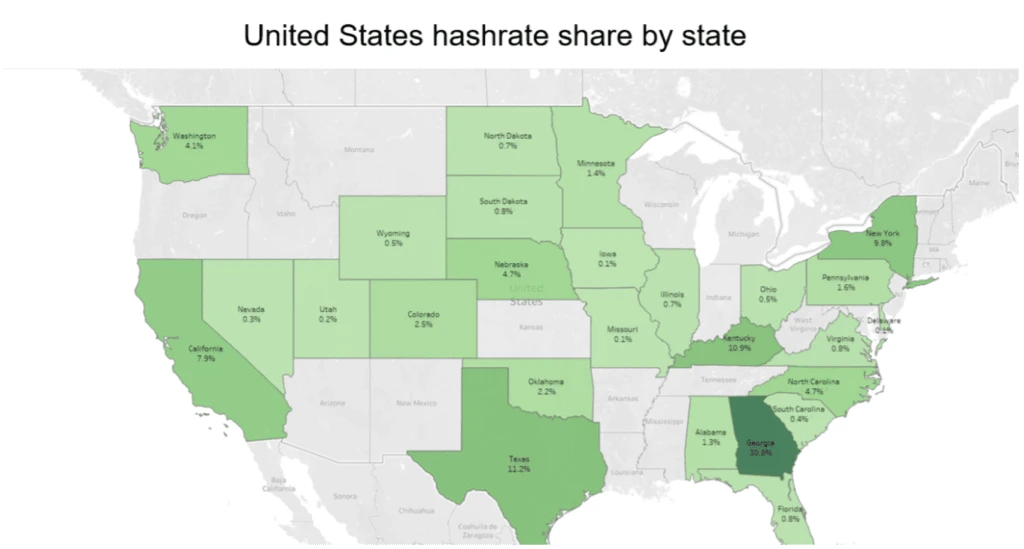

This update also brings a new addition to the tool: a regional US mining map now provides more granular insights into the largest Bitcoin mining market’s hashrate distribution at the state level. Data shows that Bitcoin mining within the US clusters around certain states, with the three largest – Georgia (30.76%), Texas (11.22%), and Kentucky (10.93%) – accounting for more than half of the country’s overall hashrate.Access to comparatively low-cost electricity, available hosting capacity, and the enactment of favourable legislation (2), (3), (4) could be factors explaining the influx of miners to those states. Significant mining activity can also be found in the states of New York (9.77%), California (7.9%), North Carolina (4.7%), and Washington (4.1%).

Defiance, methodological trade-offs, and anomalies

Most notably, however, is China’s apparent comeback. Following the government ban in June 2021, reported hashrate for the entire country effectively plummeted to zero during the months of July and August. Yet reported hashrate suddenly surged back to 30.47 EH/s in September 2021, instantly catapulting China to second place globally in terms of installed mining capacity (22.29% of total market). This strongly suggests that significant underground mining activity has formed in the country, which empirically confirms what industry insiders have long been assuming. Access to off-grid electricity and geographically scattered, small-scale operations are among the major means used by underground miners to hide their operations from authorities and circumvent the ban (5).

However, the abruptness of the resurgence raises questions that can be traced back to methodological trade-offs. A comeback of this magnitude within the period of one month would seem unlikely given physical constraints, as it takes time to find existing or build new non-traceable hosting facilities at that scale. Instead, a more likely explanation lies within our top-down research methodology which is based on aggregated geolocational data reported by partnering mining pools. This approach is theoretically vulnerable to deliberate obfuscation by individual miners who may, for various reasons, choose to conceal their location by using virtual private networks (VPN) or other proxy services. This behaviour is best illustrated by the persistently high reported shares of countries like Germany (3.06%) and Ireland (1.97%) where, as far as we can tell, no meaningful mining activities are known to exist (6).

In practice, we believe this limitation to only moderately impact the validity of the overall analysis (7) for most of the time, with the exception of sudden ‘shocks’ that fundamentally alter risk tolerance and miner expectations. The government ban being one such shock, it is probable that a non-trivial share of Chinese miners quickly adapted to the new circumstances and continued operating covertly while hiding their tracks using foreign proxy services to deflect attention and scrutiny. As the ban has set in and time has passed, it appears that underground miners have grown more confident and seem content with the protection offered by local proxy services.

Development in other major mining hubs

With the last update, Kazakhstan emerged as a popular destination for miners leaving China and quickly turned into a major Bitcoin mining centre, hosting about 18.10% of the network’s total hashrate in August 2021. Total hashrate continued to increase in September and peaked at 27.31 EH/s in October, until repeated power outages towards the end of last year, and a week-long internet shutdown earlier this year, forced miners to temporarily suspend operations. Following the electricity shortages, the government adopted a stricter stance on mining activities by increasing taxes (8) and starting to crack down on non-registered Bitcoin miners (9). As a result, total mining activity has dropped to 24.79 EH/s in January 2022, resulting in the country’s market share declining to 13.22%. It remains to be seen whether and how power shortages and political unrest will continue to affect Kazakhstan’s future as a major Bitcoin mining hub.

Russia on the other hand not only experienced a substantial drop in relative hashrate share from 11.23% in August 2021 to 4.66% in January 2022, but also a significant decline in total installed mining capacity contribution from 13.56 EH/s to 8.74 EH/s over the same period. This development seems somewhat counterintuitive at first considering that Russia was believed to become an attractive location for Chinese miners thanks to its vast energy reserves and close geographical proximity. One deterring reason could be perceived political risk given the vocal opposition of the Russian central bank to Bitcoin mining, going as far as lobbying for outlawing this activity (10). The recent invasion of Ukraine – and the resulting financial sanctions – have further added geopolitical risks that could push foreign investors and companies towards more politically and economically-stable regions to deploy their hardware.

Canada experienced only a moderate increase in its hashrate from 11.54 EH/s in August 2021 to 12.15 EH/s in January 2022, which resulted in a loss in market share from 9.55% to 6.48% as total network hashrate was growing significantly faster. Previously among the top-10 mining hubs in the world, Iran has seen a severe drop in reported hashrate from 3.75 EH/s (3.11%) to 0.23 EH/s (0.12%) in January 2022, making it join the long tail of other countries with sub-1% shares.

A new global bitcoin mining landscape

This update has brought much-anticipated insights into mining developments following the aftermath of the Chinese government ban. The geographical mining landscape has again shifted substantially, with the US now cementing its dominant position by a wide margin while other countries are only moderately growing their capacity. These geographic shifts in mining activities bring to the fore how relocations impact the overall sustainability of the network. For instance, recent research has suggested that the Chinese decision to ban Bitcoin mining has indeed worsened – rather than improved – Bitcoin’s environmental footprint (11). To help shed light on the Bitcoin’s environmental externalities, we are working towards releasing, in a subsequent update, a new model that estimates the network’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions on a continuous basis.

As part of this update, we have also implemented visual changes and other adjustments to the comparisons and methodology sections of the website following user feedback. In addition, we have adjusted the methodology for our best-guess power demand estimate by adding specific constraints to the mining equipment list to make the hardware sample more representative of miners’ current equipment portfolio. See a full list of changes.

We will continue to work with our partners and network to bring further improvements to the tool and are inviting constructive feedback and suggestions from the ecosystem. Get in touch with us.

About the Cambridge Digital Assets Programme (CDAP)

This is the first of a series of research outputs released under the Cambridge Digital Assets Programme (CDAP) umbrella. The CDAP is a multi-year research initiative hosted by the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (CCAF) in collaboration with 16 prominent public and private institutions. The programme seeks to provide the datasets, digital tools, and insights necessary to facilitate a balanced public dialogue about the opportunities and risks presented by a growing digital asset ecosystem, with the ultimate objective to help inform evidence-based decision-making and regulation through open-access research.

The CDAP’s institutional collaborators are (in alphabetical order): Accenture, Bank for International Settlements (BIS) Innovation Hub, British International Investment (BII), Dubai International Finance Centre (DIFC), EY, Fidelity, UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), Goldman Sachs, Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), International Monetary Fund (IMF), Invesco, London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG), Mastercard, MSCI, Visa, and World Bank.

References

(1) Data reported until November 2021.

(2) Asher-Schapiro, A. (2022, March 21). UPDATE 1-INSIGHT-Coal to crypto: The gold rush bringing bitcoin miners to Kentucky. Reuters. Retrieved 10 April 2022, from Reuters.

(3) GA HB1342 | 2021-2022 | Regular Session. (2022, February 17). LegiScan. Retrieved 10 April 2022, from LegiScan.

(4) Aratani, L. (2021, August 17). Why bitcoin entrepreneurs are flocking to rural Texas. The Guardian. Retrieved 10 April 2022, from The Guardian.

(5) Sigalos, M. (2021, December 19). Inside China’s underground crypto mining operation, where people are risking it all to make bitcoin. CNBC. Retrieved 1 April 2022, from CNBC.

(6) Affected countries are therefore marked with an asterisk on the mining map and a corresponding disclaimer.

(7) Greater latency in network connections generally reduces mining revenues because longer block propagation times may result in orphaned blocks that yield no reward. For this reason, miners are incentivised to choose a local proxy service that is geographically close.

(8) Sigalos, M. (2022, January 7). Kazakhstan’s deadly protests hit bitcoin, as the world’s second-biggest mining hub shuts down. CNBC. Retrieved 10 April 2022, from CNBC.

(9) Wilson, T. (2022, January 17). Kazakhstan’s bitcoin “paradise” may be losing its lustre. Reuters. Retrieved 10 April 2022, from Reuters.

(10) Pismennaya E. & Biryukov, A. (2022, January 20). Bank of Russia Seeks to Outlaw Crypto Mining, Trading. Retrieved 21 April 2022, from Bloomberg.

(11) de Vries, A. & Gallersdörfer, U. & Klaaßen, L. & Stoll, C. (2022). Revisiting Bitcoin’s carbon footprint. Joule. Retrieved from Joule.