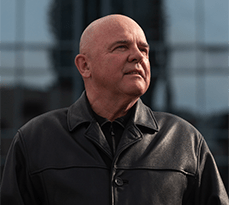

Dr Rick Colbourne, a PhD graduate of Cambridge Judge (PhD 2004), discusses his work and new book on community economic development by Indigenous peoples around the world.

Dr Rick Colbourne, a PhD graduate of Cambridge Judge Business School (PhD 2004), is Assistant Professor and Assistant Dean, Equity and Inclusive Communities, at Sprott School of Business at Carleton University in the Canadian capital of Ottawa. A member of the Mattawa / North Bay Algonquin First Nation in Canada, Rick has been involved in studying Indigenous communities around the world, and his work aims to bridge Indigenous and Western knowledge systems to develop Indigenous models of entrepreneurship and economic development. He is co-editor of a book published last year by Routledge entitled Indigenous Wellbeing and Enterprise Self-Determination and Sustainable Economic Development. Rick also is an accomplished musician, songwriter and concert promoter, having worked with the likes of Tina Turner, the Foo Fighters, ZZ Top, Iggy Pop and Elvis Costello.

We caught up with Rick so he could discuss his particular areas of research on Indigenous communities, how music influences his scholarship, and his memories of Cambridge:

How is the economic well-being of Indigenous people around the world tied to a community’s evolving model for economic development, and are there lessons to be learned by non-Indigenous people?

Historically, Indigenous peoples suffered colonisation, subjugation, integration and assimilation by merchants, traders, states and churches aimed at diminishing or eradicating Indigenous cultures, practices and identities. Postcolonial governments exacerbated these negative effects by supporting and advancing non-Indigenous interests over those of their Indigenous peoples. Indigenous community economic development represents a significant opportunity for Indigenous peoples to build vibrant Indigenous-led economies that support sustainable socioeconomic development, health and well-being; this includes asserting inherent rights to design, develop and maintain Indigenous-centric political, economic and social systems and institutions. Non-Indigenous peoples can learn from the Indigenous relational worldview, which stresses that we are stewards of the land mandated with a responsibility to ensure all of our actions and interactions are sustaining and respectful. In this, we are obligated to care for, respect, conserve and promote well-being for all people, fauna and flora on earth.

Your book ranges from North America to Oceania, so that’s a big scope. How do approaches to Indigenous economic development differ around the world?

Not all Indigenous communities share the same socioeconomic values and objectives, as Indigenous economic development is grounded in place and influenced by the interconnectedness of particular social relationships, governing institutions and values – including what is appropriate or inappropriate. For example, the Ainu in Japan had a distinct language, culture and religion, which were severely eroded by colonisation – so Ainu entrepreneurs developed business ventures whose value creation activities focused on appropriating local, regional and international tourism as a political instrument to constitute their Indigenous identity. The Osoyoos Indian Band in Canada has developed four principles to guide socioeconomic value creation activities: increase the overall standard of living for Osoyoos Indian Band members; decrease dependency on government funding; promote cultural revitalisation that emphasises their traditional values of honour, caring, sharing and respect; and increase the community’s academic, athletic, vocational and cultural education levels.

Sustainability is a theme that runs through your book. What sustainable business practices have been developed by Indigenous people that can work around the globe?

Sustainability is understood and experienced in Indigenous communities in terms of relationships to land, language and knowledge systems – with an emphasis on how these are all connected and linked to transmission of cultural values to future generations. So the rest of the world can learn from how Indigenous ventures consider how they will be accountable to their community, whether entrepreneurial value-creation activities are culturally appropriate for addressing community socioeconomic needs and objectives, and which organisational structures are appropriate for mobilising idle or underutilised community resources.

Please explain what you refer to as “Two-eyed Seeing”?

While Indigenous and Western scientific knowledge systems are both based on observations of the natural world and each are guided by distinct histories and values, Two-Eyed Seeing provides guidance on how to bridge Indigenous forms of science and knowing with western science and knowing. It accords legitimacy to all forms of knowing, asserting that divergent epistemologies are equally valuable and capable of generating further knowledge and insights. Adopting Two-Eyed Seeing involves recognising the importance of diverse knowledge systems rooted in different spaces and places and grounded in local perspectives, languages and understandings – and it encourages both Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers to identify and acknowledge the limitations and challenges inherent in focusing solely on any single knowledge system.

You seek to create “ethical spaces” for engagement that bridge Indigenous and Western ways of knowing. How do these spaces work?

These ethical spaces are based on several principles, including: local involvement in research planning and implementation, research as a process that enhances community self-determination, mutual benefit for the entire community, and respect for local philosophy and culture. The key to creating such ethical spaces is to give voice and safety to diverse ways of knowing, and a commitment to social transformation, collaboration and power-sharing.

How does your musical background influence your research on indigenous issues?

Music trained me to listen and interact collaboratively with others, and this influences how I frame and design research projects and how I engage with Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants. I now think of writing journal articles as narratives or storytelling, and am always trying to develop a strong voice through the writing. Having been a live concert producer means that I take a very systematic approach to managing my scholarship and research in terms of laying out the project plan and implementing it, and – as I did on the road as a musician – I can work at all hours of the day if need be. In music, as in scholarship, collaboration can require patience and understanding: I remember Iggy Pop running to me at the side of the stage yelling that he couldn’t hear the guitars – when actually these were the loudest guitars I’ve ever heard in my life except for the band Dinosaur Jr!

Is there anything specific or memorable about your time at Cambridge Judge Business School that you have applied to the research for your book?

The work I am doing with Indigenous peoples builds on the conceptual and theoretical foundations developed during my PhD research, where I focused on how power facilitates and also constrains learning. My thesis was guided by several assumptions, including that learning is inseparable from practice and interwoven into the range of workplace processes, activities and interactions which constitute knowledge, knowing and learning. A few other things that I remember fondly from my days in Cambridge are rowing at the St Catharine’s College Boat Club, working and socialising in the business school, biking and walking through the city, and attending Christmas pantomimes with my daughter Esmée.