Dr Joana Nascimento, a social anthropologist who is a postdoctoral Teaching Associate at the Cambridge Centre for Social Innovation (CCSI), has recently published her book titled ‘Working the Fabric’, which examines experiences of work and life in the Harris Tweed industry and draws on one year of ethnographic fieldwork in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

The book, which is available to purchase in hardback and as an e-book, touches on the culture of life in the Outer Hebrides, discussing local notions of belonging and the ways in which this unique textile industry has moved through the 21st century.

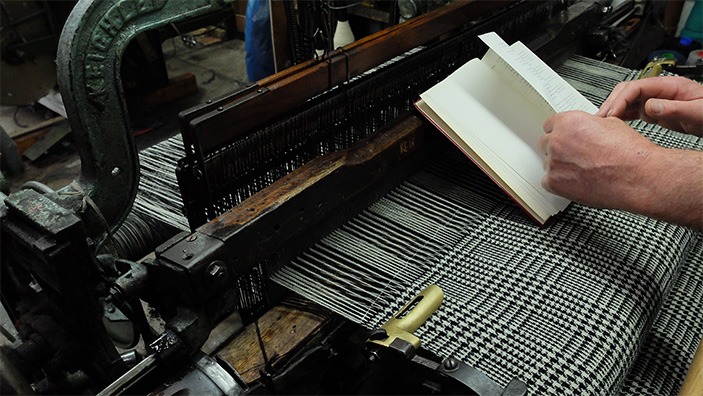

During her ethnographic research, Joana conducted participant-observation in local workplaces, learnt how to perform tasks such as weaving and warping, learnt Scottish Gaelic, conducted interviews, consulted local archives, collected audio/visual records and immersed herself in cultural events on the island.

Joana discusses the origins of the study, explores how it ties to social innovation, and reflects on how it links to contemporary work and her teaching at CCSI.

Connecting anthropology and textile production

Whilst studying for my masters, I found a book on proto-industrial textile production, which was edited by an anthropologist whose name I recognised: Esther Goody. At the time, I was thinking about what to research for my PhD. This book (titled From Craft to Industry) involved research done in the 1970s, and it made me curious about what this industry might look like today.

I thought it could be an interesting research topic; connecting with my interest in the anthropology of work and labour and thinking more broadly about questions of belonging and place-making as well.

A sense of hospitality in the Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides can be a challenging place in terms of the weather and darkness in winter, but that was made up for with the kindness and the friendships of the people that I met during my fieldwork. This sense of hospitality could also be found within the Harris Tweed industry. If you look at the definition of the industry, it says that the cloth can only be produced in the Outer Hebrides, made with 100% wool dyed and spun in the Outer Hebrides, and it must be handwoven at the weavers’ own homes. So, looking at the relationship between work and labour and questions of belonging and place-making shows us this inclusive sense of belonging that surrounded the concept of ‘islander’.

There are all these ideas around heritage and provenance that might make people believe that only weavers who are part of a weaving family would be working in that kind of role. But what I found is that the industry was very welcoming; people who were involved in the industry weren’t just locals or ‘returners’, but also people who had moved in from other parts of the UK and from Europe.

Harris tweed: contrasts with fast fashion

The kind of discussions and critiques of fast fashion that are taking place today seem to resonate a lot with some of the things that the Harris Tweed industry has already been doing for decades.

One of these is the fact that Harris Tweed is produced by order, so it is not usually produced for a lot of stock. With fast fashion, the kinds of issues that emerge in the mass production of clothes relate, in part, to the material waste, as they are clothes that are designed in a system to be quickly disposable. By contrast, Harris Tweed is 100% wool, which is seen as one of the most sustainable materials that you can use for these kinds of production.

Its track record of being able to last for decades and still look as good as new, because of the ways in which it is made, is one of the things that contrasts with some of the tenets of fast fashion.

Does Harris Tweed have a lower carbon footprint?

The cloth is exported to over 50 countries around the world, but the fact that it’s highly valued means that there’s a lower chance that it will end up in landfills as much as other textile products.

There’s always this issue that if you are producing something, you’re putting something out in the world that could potentially become just waste. The fact that this textile must be handwoven in the Outer Hebrides, made from locally processed wool, means that there’s a very localised production model that contrasts also with what happens with a lot of garment and textile industries.

If you start looking more towards the supply chain and the fact that the whole production takes place in these islands, it means that there is hopefully less of a carbon footprint in terms of transportation and there’s also more transparency in terms of the kind of conditions in which it is produced.

Challenges of global markets

Given its unique production model, Harris Tweed is dependent on fluctuations in global markets in ways that shape the potential for labour uncertainty.

There are interesting ways in which local people have navigated these uncertainties, such as the ways in which people move between different kinds of occupation – so the idea of occupational pluralism. But there’s also the danger of depopulation on the islands and so I think it’s interesting to think about those tensions: on the one hand, the industry has been really important to retain population in this region (depopulation is cited as one of the greatest threats to local life); but also, what are some of the vulnerabilities that come from being enmeshed in these global markets, exposing some of these challenges that are involved in the circulation of commodities in a globalised world?

Parallels between the Outer Hebrides and the Cambridge Centre for Social Innovation

There are many parallels from my time in the Outer Hebrides to my work in the Centre for Social Innovation. I think it’s been helpful to look back at my research and to frame it differently in relation to some of the things that we are teaching here. What can it bring to shaping the curriculum or the ways in which we supervise our research students?

It has helped in seeking to understand the complexities of the world around us and to encourage, enable and provide our students with tools and opportunities to have that critical engagement, curiosity, and openness to take on different perspectives that come from a combination of these different experiences.

Related content

Dr Joana Nascimento’s book Working the fabric: resourcefulness, belonging and island life in Scotland’s Harris Tweed industry was published in April 2023 by Berhahn Books.

Joana works as a Teaching Associate for the Cambridge Centre for Social Innovation.