Nurturing a new way to do business in healthcare for the benefit of all

Our mission

To improve access to affordable healthcare for everyone by developing, refining and supporting new, disruptive not-for-profit business models.

The challenge

Healthcare has an incredibly effective innovation engine. Its technological advances have been instrumental at increasing life expectancy by 2 to 3 months every year over the past century. However, in contrast to other industries, these technological advances have not yielded massive cost reductions that enable access for all. Quite the contrary, healthcare is becoming ever more expensive and exclusive. Technical innovation is rapid but service innovation remains slow and institutional barriers and market failures abound.

While the sharp end of the innovation plough produces fertile soil we are, as a society, not able to reap the full benefits for all because we lack effective businesses that operate in the furrow of the plough. These businesses take known innovations and integrate them into novel service models to ensure that these innovations reach society as a whole at affordable cost.

Healthcare as a Utility: Carter Dredge and Stefan Scholtes discuss the Healthcare Utility Concept with Conrad Chua.

Conrad Chua:

Welcome. I’m your host, Conrad Chua. If you’re new to the show, you can put your questions in the comments field, whether you’re watching us on LinkedIn, YouTube, or Facebook. And you can start, as always, by writing down where in the world you’re watching this from today.

Now, we’ve had several episodes on this show about the look at health care. And it’s really because in a way, every country in the world is grappling with how to deliver the best health care in the most cost-efficient way. We looked at how biotech startups can deliver better value than larger pharma companies, and we have Vanessa Dekou talking about how health service providers should look at costs.

Today our guests will look at how new business models can lower health care costs. First, we have Professor Stefan Scholtes, who is the Dennis Gillings Professor of Health Management here at CJBS and is also the director of the Centre for Health Leadership and Enterprise. We also have Carter Dredge, who is lead futurist at SSM Health. He’s joining us from the US and he’s also a business doctorate student here at CJBS.

Carter, can we start with you? Oh, one thing that came through in our previous episodes was how in health care you’ve got this tension between economic forces and the need to really preserve health and save lives of humans. You’ve spent your large part of your career in health care. How have you seen those two forces colliding?

Carter Dredge:

Excellent question. There is there is a real tension. We need to have the economic and the dispassionate economic realities of having to run businesses and secure enough resources to, again, just perpetuate the activities. We also have true human needs and real human suffering that needs to be addressed and in the broad spectrum of human suffering doesn’t always fit directly into, hey, there’s a financial or a business model to address it. So when I think about it, there’s a couple of experiences that I really draw on. One that maybe connects to how I got connected into Cambridge. So. I was serving as the chief strategy officer of a large health system, SSM Health. We employ 40,000 people. It’s a $9 billion company. We provide services to millions of people a year across numerous states in the United States. And we were experiencing some pretty intense problems in the pharmaceutical supply chain where we actually just couldn’t get access to essential products. These are like drugs that are 20, 30 years old, you know, essential antibiotics or certain types of pain medicines, etc. And the market was basically failing. There were some collaborators and I that that got together to ultimately solving it and address this problem in a meaningful way. We created a new business, scaled rapidly. We’ll talk more about it a little bit later today. But I want to tell you a little bit about some of the stories that catalysed this. So as we were looking at this problem, there was people that were sharing these harrowing experiences about how this drug shortages were just affecting real people’s lives. I’ll share one anonymised the system and the patient out of privacy. This is a real story. As we were building this business and getting to understand the issues and getting people on board, there was a leader in one of these health systems that came to us and said, Let me tell you a story and let me tell you why I’m in. There was a patient who was trying to get access to truly an essential medication, and it became very difficult to access, became prohibitively expensive and scarce, and they ultimately had to get admitted to the hospital because they couldn’t access this medication. The shortage was so extreme in this case, even the health care system couldn’t access the medication. After keeping the patient there in the hospital as long as possible, which was about 9 or 10 days. The patient was discharged. The overall situation was still bleak. The patient climbed on top of a 10-storey building and jumped off of it. It’s heartbreaking. These failures in the system are not just about economic dreck. They’re not just about. Medical costs are increasing faster than GDP. But these are real issues and these are real people getting affected. And we’ve got to do something about it. Second story. In this case is very personal to me. Because it relates to my own family. When my mother was 15 years old, she was in a very serious car accident. A car accident where the individual driving the car, which was my grandmother’s friend, had a heart attack. On a freeway like a highway system and car went out of control. Flipped off the freeway off an overpass, landed upside down on a set of railroad tracks, and my grandmother was killed. The individual driving the car was killed and my mother was left paralysed. She was trapped in the car. She was saved just at the right moment. A farmer was in his field and just happened to pull her out of the car before she bled to death. But she had massive health challenges. She just remembers waking up, staring at a linoleum floor, pinned together in a bed, and her whole world had massively changed. She had a lot of health challenges. She could still use her arms, but she had lost all of the functionality, her abdominal muscles, the ability to walk, etc. And my mother was very resilient. She became a national public speaker about overcoming adversity, and my parents got married. I was miraculously born, me and my twin brother. My parents got divorced. My grandfather moved in to take care of my mother, who was paralysed too. Three-year-old twin boys. I was one and his mother, who was by this time homebound, blind, had cardiac problems, having been born in the 1800s. So. My entire life growing up was surrounded by people who had very significant challenges. My mother had ultimately passed away from cancer and grandfather passed away from cancer. My mother was homebound, starting in her forties. So from the mid-forties until she died at the young age of 55, she could hardly leave the house. She couldn’t attend my wedding, etc. So I give that context because we are working extremely hard to figure out solutions to real problems, not because they are just disinterested, dispassionate economic challenges, but they really contain the substance of people who are experiencing real challenges and are suffering. And we need to do things better than we’re doing today. So just provide that as a little bit of context behind the purpose, behind the passion.

Conrad Chua:

Thank you so much for sharing that. That’s incredibly powerful. And I can see how in a way it’s driven what you’ve been doing and accomplishing since then in terms of the health care side. But very briefly, what got you here to Cambridge? And, you know, as a business doctorate student, what is that?

Carter Dredge:

Yeah, well, I would give some huge credit here to my friend and partner Stefan Scholtes. But if you think about it. So when we if I look back to this new company we had formed in the pharmaceutical space. We have formed a company that within 2 years had exploded in terms of growth. Within about 2 years’ time we had contracts with this new organisation called Civica Rx, with a third of the hospitals in the entire United States. For the first 18 to 20 months of the company, we were signing up equivalently of 40 to 50 hospitals a month. Just to put that in context, everyone, oh we just it grew massively. I’ve started multiple businesses. I’ve been a CEO before. I’ve never seen a business grow this fast. And as I was stepping back, we said this is something different. We hadn’t seen a business like this. It operated differently. It wasn’t, you know, set up in a traditional way. There was no equity in the business, but yet it was also different than some other nonprofits that I’ve worked in. And I have a lot of questions, and we needed time to really think rigorously with a scholarly bent of what is going on here. And that’s when my path came across Stefan at Cambridge Judge Business School and this programme called the Business Doctorate, which is a programme designed for senior executives that have built or led major corporations, but who really wants to help shape the future of thinking in an academically rigorous way. It’s a 4-year programme. I moved my family to England to work with Stefan and faculty at Cambridge Judge. And we began unpacking it layer by layer and it’s been, honestly, the most rewarding experience of my career, to be able to take the time to go through the layers, to have the best minds in the world partner with you on this. And that’s what brought me to Cambridge. I looked all over the world and it was the it was the one place that had such a unique programme that allowed me to bring the full heft of what it meant to be a senior executive and the full heft of what it meant to be a leading world academician. And that’s what brought me to Cambridge. And I haven’t regretted it for a second.

Conrad Chua:

Great. And Stefan, I wanted to ask you, though, what is the key kind of areas that you’re working with Carter on? Like, what are the big problems in health care that you guys are trying to solve?

Stefan Scholtes:

Health care is fascinating. It combines probably the most creative and innovative sphere in the scientific endeavour. As an example, as a figure of that, we are increasing life expectancy in the best performing countries by 3 months every year. And not just in the past decade or 2. For the past 150 years, every year. Get that into your head. It’s an incredible success story. So we’re innovating like mad to some extent. But then I consume healthcare in exactly the same way as my parents did. If I’ve got a problem, I go to my GP, to my primary care physician. If they think they can’t solve it, I go, they send me to a hospital. They do a lot of stuff and then I’m coming home and that’s it. So the service itself, in contrast to how I do banking and how my parents do banking, how I do retail, how my parents do retail has not changed. So at some level, a huge innovation and other incredible barriers to innovation, and that’s the service innovation. The service innovation part is what Carter and I are very interested in. How can we how can we disrupt that things without without putting people at risk? Netflix also don’t put people at risk; they are allowed to disrupt. We aren’t allowed to do that. So how do you get that going? That’s the fundamental problem, that part of my work and several other people in Cambridge as well.

Conrad Chua:

And is it a case of like just putting in more technology? We’ve seen how technology has changed various other industries. It’s brought down costs, increased efficiency. So is that the solution in health care?

Stefan Scholtes:

Interesting question, I’m sure Carter has a view as well, but let me start off. One of the issues is, what are the main cost drivers in health? So cost is very important in healthcare because it determines access, in particular in countries where you don’t have universal access at an affordable price cost. And in the NHS, we now see that as well because the NHS is overwhelmed. So people have to go private and therefore cost has to be a consideration. What are the big cost drivers? One of them is clearly an ageing population. And so lots of there are lots of studies that roughly tell us that from the age of 60 onwards, every decade doubles your health care costs. So when you’re 80, you’re 4 times as expensive as when you’re 60, on average. The second important piece is the cost of innovation has gone up through regulatory barriers and so on. In 2020 dollars, it costs about $200 million to bring a drug to market in the year 2000 around early 2000. Today, it costs 2.6 billion. That’s a fact of 13 in real terms, unbelievably expensive. But there is a third piece, because we are paying over the odds for stuff that’s no longer new. A patent as generic drugs, right? We have a social contract. We have a social contract with innovators. We tell innovators, go ahead, take the risk. And if you are successful, we give you a certain period of time where you can act as a monopolist because you have a patent. And you can basically dictate the price you want and we’re going to pay it. But after that, the contract is that once the drug is off-patent or once that period of recuperation of the risk is over, it should drop. And sometimes it does drop. Sometimes it does not drop. The FDA has a lovely graph that shows that the branded drug is about 10 times as expensive as the generic drug, but only if you have at least 6 manufacturers manufacturing it. If you have only 2 manufacturing it, it’s only half the price. So the market concentration seems to play a role. The market doesn’t seem to work really well in turning old innovations that could cost a penny into, you know, penny services. So that’s the starting position for something like Civica Rx and the starting position for our discussion of the of the health care utility model.

Carter Dredge:

And just to add on that, Conrad, Stefan’s spot on. We’re paying we’re paying a lot for things that are not new. They’re no longer novel, but they’re still very expensive. And this market concentration, we feel, is a very significant part to play in this. Here’s a couple other examples. Dialysis services: 2 firms control about 80% of the overall dialysis market. And when you compare this – and this is a statistic from the United States, but there’s other examples, other places globally, too – the private sector pays 4 to 5 times what the federal government pays for the exact same service. So delivering a dialysis treatment (dialysis takes out the toxins of your body when your kidneys have failed and before you get a kidney transplant), it’s a very high-risk thing. You need to have it 3 times a week. If you don’t get it for a couple of days, you ultimately could get very sick or die. So but this that one differential on 100 patients alone annually. The difference between what the US federal government pays and the US private sector pays is over 12 million, close to 12-and-a-half-million dollars per year for 100 people. The example of pharmaceuticals: insulin is 100 years old and insulin has become prohibitively expensive to the point where 25% of people in the United States that rely on insulin inappropriately ration it and don’t take it as recommended. And they are harmed. And in some cases they die. And this is something that was originally like sold as an intellectual property for $1, a hundred years ago to make sure it could stay accessible to everybody. Well, clearly it hasn’t. And you have 3 firms that produce the vast majority of the insulin and you have 3 distributors in the form of a pharmacy benefit management company that control its distribution. And so these oligopolies just continue to concentrate these activities. We could go on. There’s 2 firms that control 90% of the global market of linear acceleration to treat cancer. And you want to talk about a disparity in access statistic. There’s a little over one million people in the state of Rhode Island in the United States. I believe there are approximately 12 linear accelerators in that market. There are 117 million people in the country of Ethiopia. And there’s one.

Conrad Chua:

So what can we do about this? You know, is this something that requires global intervention to break up oligopolies and stuff like that? But at the same time, would that disincentivise innovation? And I think this is a good time for maybe Carter, you want to talk a bit about that health care model that you and Stefan have been trying to develop.

Carter Dredge:

I think this is a perfect time to talk about that because we’re not just going to pontificate on the problems, but we really feel we have some strong thinking, not only thinking, but action and activity that is addressing these types of problems. So but if we frame it up, you know, a good question. And again, I’d credit my time at Cambridge and working with people like Stefan and others about the power of the right question. Here’s the question, that we certainly think about a lot: how can we harness the ingenuity of private sector entrepreneurial innovation? How do you get people who have passion or thinking about something and get that ingenuity but still ensure an affordable and equitable access for everyone? How do you take ingenuity and not just result only in profits, but actually access true access. And the conclusion that we’ve come to, particularly in health care, particularly where we have old established ideas that are getting, we’re paying a lot for them. We don’t just need new businesses. We need new business structures. So definitely, we need new types of businesses to get at this problem. To put a little bit more concreteness to what we’ve been talking about in health care. Health care’s a little bit different. There are other areas where you can’t use that as a crutch. We need to use that as a springboard to then use those differences to do different things. Well, we’re talking about high stakes services. These services are essential. Normally, if you feel you’re not getting a good value prop, you do one or two things, go somewhere else or go without. In an essential health care service to live the second option is not an option unless you just choose to die or be in incredible suffering. The second because of massive concentration, and when you only have 2 or 3 firms in the entire world that do something, your ability to go somewhere else is extremely limited and they’re all in the same options set. That creates problems. And then think about this. We’re high stakes. If you get screwed up, people die or organisations get sued. They’re really complicated. This isn’t just a decision of, well, I’m going to switch from Netflix to Disney Plus or another streaming service. And if you didn’t like it, you switch back. It’s not we’re talking about. Switching could take years with how complex these services are. An organisation choosing to switch a PBM, the process typically takes over 2 years for them to make that decision and make that transition and that switch. You can’t always switch back. And lastly, there’s a lot of talk about innovation, about the consumer. And we do need more direct patient and consumer engagement in health care. But with many of these services, the decision maker first are institutions. Institutions are the ones that are choosing to include it in the options set or not, whether that’s a federal government, whether it’s a private insurance company, etc. But what’s covered, what’s an official health care service, is many times determined by an institution and therefore to overall to creates to enter into a market that has massive scale economies, we have to figure out how to do this, not just out of someone’s garage with an entrepreneurial slant, because it’s high stakes, it’s high risk, and in some cases may require hundreds of millions of dollars of capital to do it right. We have to figure out how to engage multiple institutions, multiple organisations that are already large, that already understand the complexities and the regulations of health care, and have them all work together to actually do something. We call to disruptively collaborate.

Now, this in a very brief sense, as we unpack this, this notion of how do we get lots of people to work together to collaborate differently. I wonder if I could just toss really quick to Stefan. Stefan, can you mention just a brief mention about disruptive innovation and compare and contrast this about what we’re talking about with disruptive collaboration? They’re related, but different. And then I think we can continue to push, push forward and thus get into the actual model. And then we can also get to some of the really good questions that are kind of coming through as well.

Stefan Scholtes:

I can do just a brief spiel on disruptive innovation for those people who don’t really remember it or don’t know it. It goes back to Clayton Christensen from Harvard University, from Harvard Business School. It’s a concept that tries to understand the dynamics that lead to disruption, like going from Blockbuster videos, to DVDs on the doorstep, to actual streaming. So where whole industries change and sub industries disappear and are replaced by others. And so one way you could think about that is you disrupt an industry head-on. You’ll say, okay, you have this model, the Blockbuster model, and we come in and we compete with a completely different model head-on. That’s not how disruption normally works, because the incumbents are too powerful. They would destroy you if they would see what you are doing. They would realise what you’re doing. So really, disruption often happens by stealth. By people coming in and working on such problems for which they have better solution than the incumbents. And these sub problems on actually these sub markets are not of interest for the incumbents, probably because the margins are not large enough. So they are actually not going to fight these entrants for the new entrants work on these small problems. Get this niche organised and then build with a new operational model, build up and destroy the incumbents. And so that is a kind of dynamic I think that we can learn from. But that doesn’t necessarily work without some thought in health care. So what is that service, that entry service for disruptor, what is that? Call it the rebar coming from the steel industry. So what’s the niche market that you can enter without being killed and without killing people or without harming people in the health care context that allows you to hone your new model with a view of then scaling it up and replacing an old one.

Conrad Chua:

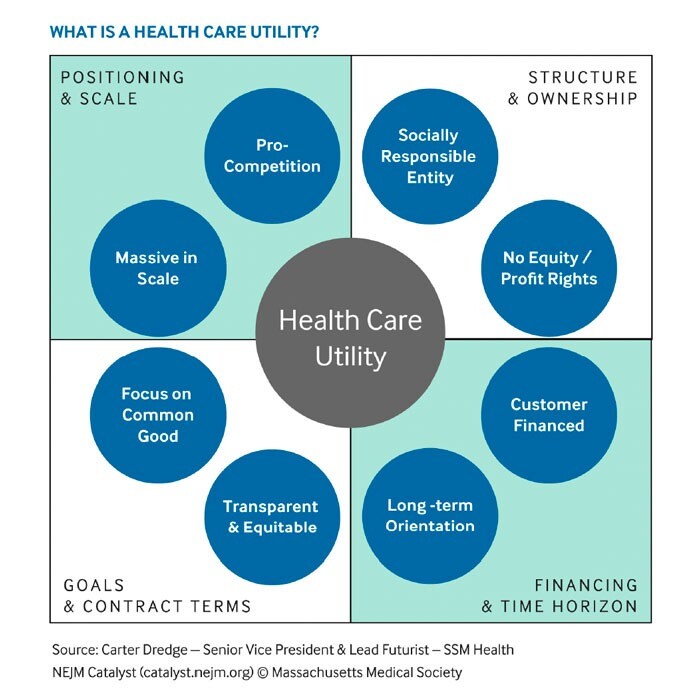

Maybe this is a good time to talk about this this chart that you guys have, which is what you call the healthcare utility model. Carter, do you want to talk about this?

Carter Dredge:

So how do we enable this kind of entry into these complex spaces in a rebar type sense in a lower end of the market to work our way up? The perfect petri dish of this case was generic drugs in the United States. But I will say this model, which we’ve developed and written about and spoke about and developed at Cambridge, is applicable to far more than just pharmaceuticals and to far more than just a US health care context. That’s one of the reasons we’ve turned it into a model and we’ll talk about it now. And if any of you like us, they’re watching this, listening to this and you want more information, we have a couple of publications that go into this model in detail. They’re published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Catalyst. And when the editors realised what we were doing, they put them in front of the paywall, which means you can access them without a paid subscription because they felt the societal benefit was significant. So if you just Google my name, Stefan’s name, plus the “health care utility model” or “disruptive collaboration”, you’ll find them. So here’s how the model works. Okay. I’m going to go from the top right quadrant clockwise first. How we set these businesses up is if no one owns them, there’s no equity. We didn’t take money from venture capital that’s required a later exit to sell the business. No one owns the business. It’s set up as a 501c4 social welfare organisation, and we have philanthropists on the board so that the business doesn’t change course after it just grows big and then decides to sell itself. We’ve taken that off the table. No one owns the business, so we’ve set it up that structurally we can align the business with the interests of patients directly. Number two, where do we get the money? We get the money from the customers and more specifically, the institutional customers. In the case of Civica Rx, which works with inpatient essential generic drugs, we raised money from hospitals directly and philanthropists when we launched the business. We went out and raised $100 million, $70 million from health systems, $30 million from philanthropies. And we raised money from the customers because then they’re not trying to arbitrage and just get a return only on the financing. They’re not a bank. They’re trying to solve a critical problem where we have a shortage of drugs that are essential to our business and to patients. So no one owns the business. And we raised money from the people who need the services to be stable and affordable. So we align the incentives structurally and financially. Bottom left quadrant. The reason we call it a utility is because the way it contracts and works with its members and the individuals in the market, and that is under the same transparent, low cost terms. It’s not about finding one customer segment to squeeze out a little bit more margin. It looks at the problem. It understands the cost structure. It plays very big and very long. Again, within a short period of time, we were playing at a third of the entire in-patient hospital market in the United States. And it sets a single, transparent, low price for everybody. So just like saying, how do we deliver essential water? How do we make sure people have electricity? How do we make sure people have access to essential medicine to live in the lowest, sustainable way? That’s how we contract. And it’s one of the reasons why it grew so fast, because as Stefan and I were working through and pulling through. What were these reasons in this case? The sales process was very different than anything else. When you’re sitting across and saying, Should I join Civica, you’re not asking “am I sure am I getting a really good deal”? You’re getting the exact same deal as the largest healthcare system in the United States, and you’re getting the exact same deal as everybody. And then lastly, the market positioning and scale. This is not a traditional for profit entrant. It’s also not an entity of the state or country. It operates in a dynamic position in a marketplace, but it does so in a cost-minimising, access-maximizing way rather than profit-maximising way because there’s no owners and the people loaning the business money are doing so to get low cost, affordable access to the products and services they need. It creates a virtuous cycle. But instead of gaining scale and then creating the ability to charge premiums and extract excess rents. It creates a virtuous cycle to deliver essential health care services to the people who need it the most. At scale, delivered consistently and transparently. And what it does is it takes it brings innovation to new ideas. These weren’t new products. These are 30-year-old products. And yet we had people coming out of all types of places to work in an innovative environment. We rekindled innovation on a 30-year-old drug. Because we had the ability to break through barriers that were preventing access. It was exciting.

Stefan Scholtes:

I’ll add one comment on that, which is the importance of scale. This is really critical in many aspects of healthcare. We have economies of scale. We can hardly name anything where there aren’t economies of scale. People know that you need to do enough surgeries of a certain kind to get to get the right quality outcome and so on. But if you think of the digital play, obviously everything is a scale play. If you think about dialysis, rolling it out, dialysis centres, or at-home dialysis across the nation, that’s a huge scale play. So economies of scale are everywhere when they are, but with whom? All they share is the question who benefits from economies of scale? You could say it’s those who were first in the game. They were first. They did the small piece that were more costly and therefore they should reap all the benefits of scale. That’s not what happens here. The moment a new health system joins Civica, scale increases, the cost comes down of the product, and that coming down of the cost is shared with everybody equally. Everybody benefits. It’s a very important part of the dynamic.

Carter Dredge:

And for those of you that may be asking the question “can this be repeated”? The answer is yes. First, we went from inpatient drugs to retail drugs. And while that may not sound big, it’s actually quite significant because the customer base was entirely different. Retail medicines in this case are predominately they’re got from a local pharmacy. And in fact in this case the people incurring the institutional cost are not hospitals, they’re insurance companies. So we actually formed a second company called Civica Script, which in this case we work with 23+ large insurance companies. And just like how in Civica Rx, we aggregated a third of the hospital inpatient capacity, in Civica Script we aggregated over 140 million covered individuals. Which is approaching half of the population of the United States. Little less, but huge. So that enabled us to now we’re going after and we’re going to be producing a low cost insulin. We’re going to drop the price of insulin from your standard typical market price by 85 to 90%.

Conrad Chua:

So for those who are interested, that’s I think that’s the paper that’s in the New England Journal. And I think it’s good to get a couple of questions now of this for a few questions. I’ll just pick this one from Romit about generics and distribution in low income countries. How can this model bring benefits to low income countries, not just for people in the US or in Europe?

Carter Dredge:

We’re actually getting a lot of interest from people all over the globe about this notion of, if you could pool the collective scale to create a stable contracting pipeline and a stable supply – you know, there’s people right now who are exploring instead of looking at entities as large corporations, you could look at them as purchasers of smaller countries, you can look at them as other organisations within… – the idea is who is incurring the institutional costs to then pool those together to enter into a stable contract in there. We talk about that we call minimum viable volume contracts. How do you aggregate demand to stabilise supply? So just think about whatever it is, whatever your unit is, whether it’s at the entry of a country, an organisation, a community. It’s about aggregating demand and then making sure the model doesn’t just advantage disproportionately one group selectively over another, because that erodes trust and it has partnerships that blow up. So one key point. This is different than an association because it’s an operating entity. This isn’t just, hey, let’s share best practices and figure this out. But at the same time, it’s about having a structure that keeps people in the game for the long term. Because no one is this is advantaged or disadvantaged over another, and that has that has massive applicability far outside of the US for outside of pharmaceutical stuff.

Stefan Scholtes:

I mentioned the importance of scale. When you think about a health care utility, the second most important question is who are the members? So Carter mentioned that the members, the customers, the funders, they are all the same, right? The members in Civica Rx are hospital systems. Because they are the customers. The members in Civica Script are insurance companies because they pay the bills. Could countries be members of healthcare, utilities? We’ve been exploring this idea with people from Nigeria and from India around cataract surgery. Cataract surgery is one of the most standard surgeries you could think of in the world. It is the most-done surgery in the world. Yet there are lots of countries where it’s very hard to get access. It’s very hard. There are models of it, in particular in India. I’m thinking particular about a company called Aravind that have basically commoditised cataract surgery. So now the question is how do you deploy it across the world? And potentially a health care utility with individual countries as members could be a way of doing that. We haven’t fully explored that yet. Just to give you a few nuggets, maybe you can think it through some of the some of the you some of the listeners can think it through and take it forward. It’s a wonderful question, a very interesting idea.

Conrad Chua: You talk a lot about its scale and how this model works on quite well-established treatments, cataracts, insulin, for example. And Mansa asks, what about like rare diseases or gene therapy? So this is more cutting edge. Can this be applicable? Can this model be applicable there? And does that help in terms of access, again, to low income countries?

Stefan Scholtes:

The rare diseases are even rarer if you don’t aggregate demand. The only way of working with real diseases is to try and get the whole world as your customer. And so I think there’s an element of thinking this through in the rare disease context as well. I mean, this is not to do with the expanded access programme. That’s a different type of idea. And there are plenty of good, good ideas in that context. But I think the fundamental challenges, if you are in a rare disease context, you’ve got to aggregate demand. And again, that’s what the health care utility does. It’s the size, it’s through demand aggregation.

Carter Dredge:

So there’s an element that you have to aggregate demand. The one thing about developing a new product is there’s also a lot of significant risk. Which also might demand some significant risk premiums, which may or may not require a more like a private capital to bear that risk. So it’s a good question. So, you know, one thing we’ll have to continue to ask is what are the boundary conditions of where this model can be applied? I think that, you know, clearly that the initial use case had to do with the central bank. But let me make a connection to this. How do we connect commoditsing essential innovations with novel innovations and fuelling those? And it doesn’t have to necessarily be you use the same model. Because if you think about it, we’re spending huge amounts of excess on old ideas. As we can use it, utility to scale those more affordably, more accessibly, we create savings. Those savings when they’re created can be used to deploy to solve other novel problems. There’s the virtuous cycle. So putting it simply, I view the innovation opportunity before us as we need 2 engines for innovation. We need an engine to break barriers that have not been broken to plough the ground. This is where venture capital, private innovation, government spending on things that are totally unproven and untested start to make sense because we have to reach farther. And then. To basically enforce, if you will, appropriately, the social contract. Once the ground has been ploughed, once the furrow is there and we need to get to the water at the end of the row, we need a business model that gets it to everyone sustainably and effectively. That’s where utility comes in. So right now I’m very comfortable of thinking about the process of once a drug becomes the standard of care. How do we get it to everybody? And that’s very squarely in the line of a health care utility. But I’m definitely not opposed to saying, “Hey, who can think of these new things?” Maybe it’s a rare drug, maybe it’s something else. I just want to make sure that we say the key in health care and this is one of the biggest things we’ve learned is you need to match the right problem with the right business model and when you mix those up. You get really high costs or really poor results in another way because it doesn’t work.

Conrad Chua:

Sonia asks, so is it true that there’s no incentive for the health care industry to provide health care? It’s all about trying to treat you when you’re sick or you’re close to death and not try to increase your health per say.

Stefan Scholtes:

I would say that is spot on. A big problem in the NHS is that we have a national illness service, not a national health service. We come in when it’s way too late. The amount of money that goes into trying to prevent illness is minuscule compared to the amount of money we spend on trying to cure when it’s too late. So you are absolutely right Sonia.

Carter Dredge:

Yeah, I agree. We have these alternative payment models to try to align incentives. One way I would think about this with the utility, another word we use to describe utility is an alternative production model. You have to change the incentive to get the outcome in every system. Someone’s designed to get the outcome that it gets. And you are correct. If we’re going to get more holistic prevention, wellness upstream activity, we’re going to have to continue to change the business models. And one thing about this is it allows you to be more discrete and proximate rather than trying to boil the ocean, which has been tough. But I want to I want to add one more comment to that. So it’s a very important point because health care utilities can be used, we believe, to correct market failures. That’s one aspect. They could potentially also be used to develop new markets. Well, there aren’t enough incentives for market for market forces to actually react, respond. So this would be a use case. Prevention would be a potential use case for health care utilities to create a market that we need. But we don’t have the incentives for private enterprises to come in effectively and efficiently to solve the problem we have our country.

Conrad Chua:

So thank you so much for that wonderful conversation. And I want to thank both Stefan and Carter for sharing those insights. And I think it’s in everybody’s interest that something like the health care utility really takes off because ultimately all of us, whether we like it or not, will have to deal with the health care service at some point.

This is a joint global strategic initiative between Cambridge Judge Business School, Intermountain Health and SSM Health.

The vision – healthcare utilities

Utilities, like water and electricity companies, do not offer a tailored service to a chosen market segment but instead deliver a high-quality product or service to all customers at equal and low cost. Our vision is to develop rapidly scalable not-for-profit business models for service innovation in healthcare, based on the concept of a healthcare utility. These business models radically change the way we deliver healthcare and boost competition in a societally beneficial way, without limiting access or increasing costs.

A healthcare utility is a self-sustaining non-stock corporation with a social mission, formed by healthcare institutions to commoditise essential products and services and provide them at the lowest sustainable cost, using a focused, transparent and scalable business model.

The business model addresses 4 key components:

- structure and ownership

- financing and time horizon

- goals and contract terms

- market positioning and scale.

Reports

Doctoral Thesis University of Cambridge | June 2024

Structural Transformation in Health Care: Disruptive Collaboration Through Health Care Utilities

By Carter Dredge

Articles

NEJM Catalyst | 21 May 2025

Changing the Script on Drug Pricing: A New Type of Supplier Creates Savings for Patients and Plans

CivicaScript, a healthcare utility dedicated to lowering prices in retail pharmacies, reduced the cost of the cancer drug abiraterone acetate by 92% for payers and 64% for patients, showcasing a scalable and sustainable alternative to traditional pharmaceutical supply chains.

NEJM Catalyst | 20 September 2023

Vaccinating Health Care Supply Chains Against Market Failure: The Case of Civica Rx

This article presents the first empirical evidence that Civica Rx, a healthcare utility established to address generic drug shortages in hospitals, significantly enhanced access and reliability while providing lower prices for critical medications across its member U.S. health systems.

NEJM Catalyst | 12 October 2022

How Venture Philanthropy Can Disrupt Health Care: Lessons from Civica Rx

A small cadre of business-minded foundations collaborated with the private sector to upend rising drug costs and potentially transform the health care industry.

NEJM Catalyst | 29 March 2022

Disruptive Collaboration: A Thesis for Pro-Competitive Collaboration in Health Care

Leaders at Civica Rx have developed a potentially disruptive health care business model that enables private-sector efficiency and public-sector societal equity at scale.

NEJM Catalyst | 8 July 2021

The Health Care Utility Model: A Novel Approach to Doing Business

Leaders at Civica Rx have developed a potentially disruptive health care business model that enables private-sector efficiency and public-sector societal equity at scale.

Cambridge Judge Business School Case study

Civica RX: Collaborating to disrupt healthcare

This case study was written by Dr Lisa Simone Duke, Researcher, Carter Dredge, Senior Vice President & Lead Futurist, SSM Health, and Professor Stefan Scholtes, Dennis Gillings Professor of Health Management, University of Cambridge Judge Business School.

Journal of the Catholic Health Association of the United States | Fall 2022

What Is the Health Care Utility Model, and How Can It Transform Health Care?

A Q&A With SSM Health’s Lead Futurist Carter Dredge

Videos

NBC News | 27 June 2022

Discussing societal needs and economic growth at Aspen Ideas Festival

Three disruptive business leaders, Ashley Bell, Carter Dredge and Rodney Williams, all part of the Aspen Global Leadership Network, address societal needs at the Aspen Ideas Festival in a conversation moderated by NBC News President Rebecca Blumenstein. NBCUniversal News Group is the media partner of Aspen Ideas Festival.

Case studies

- CivicaRx is a disruptor in the US generic medicines market. Its focused mission is to make generic medicines accessible and affordable to everyone.

- CivicaScript is a subsidiary of CivicaRx, focused on bringing lower-cost generic medicines to millions of people across US.

- Graphite Health is a not-for-profit company with a mission to establish a trusted digital ecosystem composed of an interoperable data platform and application marketplace that will drive the digital advancement of healthcare for patients An Introduction to Graphite Health

Initiative leads

Carter Dredge

Executive Director, Intermountain Health Institute

BusD (University of Cambridge)

Stefan Scholtes

Dennis Gillings Professor of Health Management

PhD (Karlsruhe University)

Contact us

For more information, contact Stefan Scholtes.