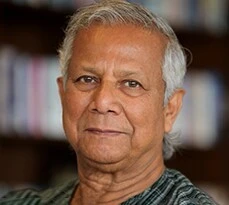

Professor Muhammad Yunus, who won a Nobel Prize for pioneering microcredit in Bangladesh, tells the CJBS Perspectives video series on leadership about how he was inspired to provide financial services to the excluded.

Professor Muhammad Yunus, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for pioneering microcredit and microfinance, says he was motivated by a belief that traditional banks were doing everything backwards – including lending money only to people who already had money – so he decided to pursue an alternative path. The Bangladeshi social entrepreneur and economist founded the Grameen Bank for microcredit in 1983 and later launched the Yunus Centre, a Global Hub for Social Business.

Professor Yunus was interviewed via video by Paul Tracey, Professor of Organisation & Innovation and Co-Director of the Cambridge Centre for Social Innovation at Cambridge Judge Business School, as part of the second series of CJBS Perspectives: Leadership in Unprecedented Times, a series of talks with prominent business leaders and other public figures organised by the Alumni & External Engagement and Executive Education teams at Cambridge Judge.

Here are edited excerpts of their discussion:

What motivated you to calculate new ways of measuring financial exclusion?

I saw loansharking that was going on in the villages of Bangladesh, so one simple idea came to my mind: ‘Why don’t I lend the money myself, and the person who borrows from me will be protected from the loansharks.’ The money needed was not very much. And it became very popular. I thought banking was designed in the wrong way – lending money to people who had money rather than people who don’t have money. The bankers laughed at me. They said: ‘These people are not creditworthy,’ and I said: ‘Should you tell them they’re not creditworthy or should they tell you you’re not people worthy? Why don’t you fix your organisation so you become people worthy.’

How has the microlending model changed since 1983?

Not much. In the beginning we changed things a lot, but then it took shape after about two years of our work. I had no background in banking – I just wanted to help people so they could pay back easily. Since I didn’t know any banking, whenever I needed a procedure or system I looked at the conventional banks and did the opposite: they go to the rich, I go to the poor; they go to the city centre, I go to the remote villages; they go to men, I go to women; they say people should go to the banks, I said banks should go to the people. The only recent change was made due to the pandemic – it became virtual banking. And that was a big departure, but once the pandemic is gone we won’t go back because it worked so well. So now we’re asking why we should have physical branches and people.

What led you to focus on women as a big part of your mission from the very beginning?

Banks had denied financial services to about half the population in the world. I said to them: ‘You don’t only deny access to poor people but also women, not even 1% of your borrowers are women, so something is desperately wrong with your system.’ Some women initially said that we should hand the borrowed money to their husband because they had never handled money in their lives, but I told my female students to always remember that this is not her voice. Many of these women have been invisible, and money will make them visible, so be persistent and some day the real person will overcome all the fears that surround them. We worked continuously for six years to get to 50%-50% men and women, and then we got to 97% women.

Beyond the issues with the financial system, what other types of systemic changes are needed including at the governmental level?

Government has the power to develop an environment for people to do the work; government doesn’t have to do the work. For example, we don’t have social businesses for pharmaceutical companies. If you had a social business for pharmaceutical companies they wouldn’t need to make money, because their business is to protect life. The problem with charity money is that it can be used only once; with a social business the money goes out, and comes back, and can then be used again.

Do you have any final thoughts for students who may soon be graduating?

Young people are very powerful people. They now have technology in their hands that no generation ever had before. So I urge young people to ask themselves one question: ‘What am I going to use this power for?’ Everyday they have to make use of it. They have an opportunity to do things that were never done before, because young people have minds that are not contaminated. It can be a beautiful world, the world that you create. Imagine the world you want to make, and if you imagine it will happen.