The current tennis scoring system – point-game-set-match rather

The scoring system used in tennis – point-game-set-match rather than total points as in basketball – significantly improves the chances of an underdog winning a match at the upcoming Wimbledon championships, according to a novel scoring model developed by a University of Cambridge academic known globally for his climate change model.

“Tennis has a weird scoring system,” says Dr Chris Hope, Reader in Policy Modelling at Cambridge Judge Business School, in a blog post announcing his findings. “This leads to lots of excitement, as mini-dramas unfold near the end of many games and sets. But it can also lead to unfair results.”

Hope, whose PAGE (Policy Analysis for the Greenhouse Effect) model on greenhouse gas emissions has been used extensively by the US Environmental Protection Agency and other official bodies, turned his modelling expertise to tennis in advance of this year’s Wimbledon, which begins on Monday 2 July 2018. Hope previously produced a model on top-flight English soccer for a research paper entitled “When should you sack a football manager: Results from a simple model applied to the English Premiership“.

Hope’s PAGE model estimates the social cost of carbon dioxide to “help policymakers understand the costs and benefits of action and inaction”. His new tennis scoring model has more modest aims to generate numerical debate about an ancient sport whose most prestigious event has always been big on numbers. A whopping 33,000 kilogrammes of strawberries drenched in 10,000 litres of fresh cream were consumed during last year’s Wimbledon, when the fastest ladies serve was 121 mph (195 kph) by Petra Martic of Croatia, says the tournament’s website.

“The modelling techniques I use to look at climate change seem to be quite applicable to sports statistics,” says Hope, a keen junior tennis player in his youth.

A spin on the scoring system

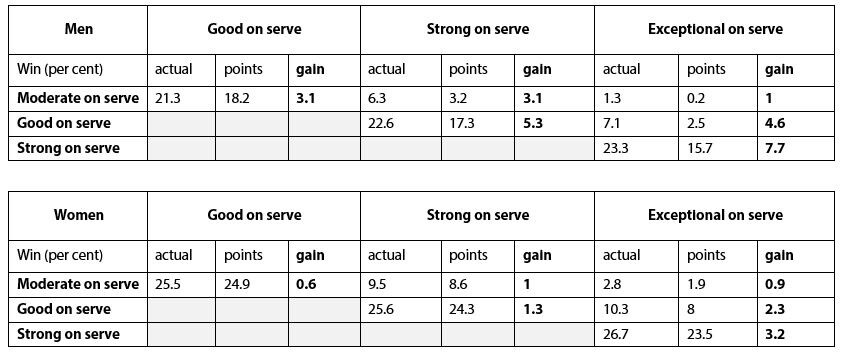

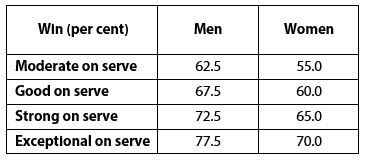

So, Hope looked at the difference between a simple points-based tennis scoring model and the current scoring system – focusing on whether a player and the opponent are “good on serve”, “moderate on serve”, “strong on serve” or “exceptional on serve” (based on ATP and Women’s Tennis Association statistics).

For both men and women, Hope’s model found, the chances of the underdog are boosted most in absolute terms if a player who is strong on serve plays one who is exceptional. For example, a man strong on serve wins 23.3% of his matches against a player exceptional on serve under the current system, but only 15.7% under the simple points-based system; for women, these percentages are 26.7% and 23.5%. The effect is larger for men because men win on average about 8% more points on serve than women.

In relative terms, the underdog’s chances are boosted most if a player who is moderate on serve plays one who is exceptional – although on the lightning-fast grass courts of Wimbledon a player who is moderate on serve wins matches very rarely against one who is exceptional under either the current scoring system or the simple points-based system.

“For men, a player who is moderate on serve against one who is exceptional will win 1.3% of the time with the actual scoring system against only 0.2% of the time if the scoring were points-based,” Hope found. “So his chances increase about six-fold. For women, a player who is moderate on serve against one who is exceptional will win 2.8% of the time with the actual scoring system against 1.9% of the time if the scoring were points-based. So her chances are increased by half.”

It’s long been known that in 5% of matches on the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) Tour the loser wins more points than the winner, which can occur when the winner conserves energy in sets or games the player can afford to lose (for example, in a 7-6, 7-6, 1-6, 6-4 match).

“That is not what is being investigated here,” says Hope, whose model assumes that each player has a given percentage chance of winning a point on serve that remains constant throughout the match with each match simulated 100,000 times so the model’s winning-percentage tables are highly unlikely to be more than 0.2% wrong at worst.

Advantage: underdog

Hope’s model is based on comparing results under the current scoring system to a system in which the players take turns to serve six times (like an “over” in cricket), up to 25 times for men and 15 times for women – with the total points then added up. In this simple points-based system the winner is the first to 151 points for men or 91 points for women, with a coin toss to decide 150-150 (men) or 90-90 (women) ties.

“The maximum match length of 300 points for men or 180 points for women is the same as the average length of an actual five- or three-set match, which average 60 points per set,” says Hope.

Hope looked at two British players at this year’s Wimbledon to see how their chances might be affected.

In the men’s tournament, Kyle Edmund (now ranked 18th by the ATP tour) won 67.5% of his points on serve on grass in 2017, putting him in the “good on serve” category for men. The current scoring system will work against him by 3% in the early rounds, when he would likely be favourite to win, but the current system gives him a boost of 4% to 5% “if he gets through to later rounds when he is more likely to meet a player who is strong or exceptional on serve,” says Hope.

Likewise, Johanna Konta (ranked 22nd by the Women’s Tennis Association) won 63% of her points on serve last year, and will probably win more on Wimbledon’s grass, which puts her in the “strong on serve” category for women. She is, therefore, 1% to 1.5% less likely to win in early rounds against lesser opponents under the current system compared to points-based scoring, but gets a 3% boost if she gets to later rounds where she is more likely to meet a player who is exceptional on serve.

Edmund was knocked out in straight sets in the second round of the 2017 Wimbledon tournament, while Konta lost in the semi-finals in straight sets to five-times Wimbledon singles champion Venus Williams.

Britain has a long history of rooting for the underdog at Wimbledon – at least homegrown underdogs. Until Andy Murray won the men’s final in 2013 (repeating in 2016), there had been a 77-year British title drought since Fred Perry won the men’s Wimbledon singles crown in 1936, and the last British women’s singles winner was Virginia Wade in 1977.

Before Murray’s triumphs, there had been repeated heartbreak for British fans as Tim Henman was knocked out in the semi-finals four times between 1998 and 2003 – drawing moans from the hordes of fans watching a big TV screen on a grass banked area at Wimbledon on what was then known as “Henman Hill” and later renamed “Murray Mound”.

Break point for success

“The excitement that the current scoring system brings, and the advantage it gives to the underdog, might not be a bad thing given the dominance of certain players, men and women, at the top levels of tennis,” says Hope. “In fact, other sports could probably learn from tennis and its scoring system – including basketball, which is sometimes boring, and cricket, which seems to be on a perpetual search for a livelier format.

I don’t think for a minute that these findings are going to change the current scoring system for tennis. But as a professional modeller, I think it’s useful for people to understand how unfair the scoring system potentially can be.

The two tables below show the percentage of matches won by women and men with the present scoring system (actual), a points-based scoring system (points) and the gain for the underdog (gain), for a player who is either moderate, good or strong on serve (shown in the rows) against a player who is good, strong or exceptional on serve (shown in the columns). The third table shows the categories on serve for men and women. (View screen-readable tables on the original blog post)